Sunday, October 31, 2004

This is a contribution to the Ecotone topic, ENERGY OF PLACE.

Late October, 2004. Small town in Vermont. Outside the window, bare maple branches toss in a gusty wind. Beneath them, a carpet of russet, beige, brown leaves, drying, and a crimson burning bush. It’s Sunday morning, and I can hear the wind, and a four-wheeler recently purchased by a neighbor, running up and down the street for the entertainment of his two daughters, bundled into the vehicle. This is new in the past few weeks, but the sound of internal combustion engines is all too familiar; a month ago, the sound would have been a lawn mower, or the leaf-blowers from another neighbor’s lawn service.

I feel a little slow and thick this morning; maybe it was last night’s wine or the lingering conversation, which tipped, teeter-totter-like, between talk of middle age - physical complaints, aging parents, teeth, and medical care – and politics, America, the future. The greyness of the late fall outside has a similar, worried torpor. We wait for Tuesday to know our fate, like the newly shown hostages, young UN workers captured in Afghanistan. I went outside to see if there was any Swiss chard left in the garden, and startled an unfamiliar cat, who stared at me from my own back porch as if I were the intruder.

In my other home, a different scene would be unfolding. Montreal wakes up about now on a Sunday; last week at 9:30 I was on my bike riding from the Plateau into downtown, on my way to the cathedral, marveling at the empty streets. By ten or eleven, other cyclists are emerging, necks wrapped in scarves; people are starting to enter the park, hand in hand, children in strollers. No one is rushing, although the roller-bladers glide by like water. Café owners and shopkeepers begin to come out, sweeping the streets, greeting their neighbors, ready for the first customers of a day that will stretch into night. There will be a few cars by now, but rarely the sound of a car horn. Montreal is the quietest big city I’ve ever been in.

What is absent is not energy, but anxiety. The energy I notice is mostly human-powered, and on a human scale: people walking, biking, talking, at the pace of a heartbeat or a footstep, or the lift of a coffee cup to the lips. The frantic, endlessly circling four-wheeler would make no sense there; even the boy who spends long hours in the park bouncing his mountain bike on the children’s big flat rocks in the playground is not aimless: he is practicing a skill, and he’s intent on it, as are the skateboarders who take over the large shallow children’s wading pool as soon as it’s drained in the fall. People stroll together in the parks, talking and smiling: women friends, male friends, couples, people with dogs who seem to be friends. And people aren’t afraid to be alone: everywhere you see them, quietly sitting, looking, drinking coffee, smoking, or, most often, reading.

I’ve gone back and forth enough now to know that the difference in energy is not imagined but real, even though I can only see its pathology or health through symptoms, some subtle, some not so. The anxiety, stress, and fear that insidiously worked on me before are at least obvious to me now; even when I am in the midst of them I have some choice about what to take in and what to keep at bay, what to fight or challenge and what to ignore.

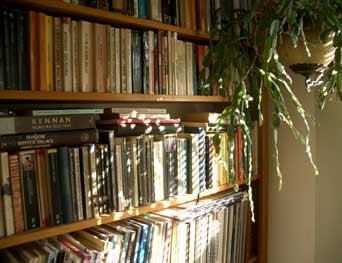

What keeps the spirit alive? Books and art; creativity and spirituality; music and color; sensuality, nature, relationship. We should be glad for this virtual place, where these things are still topics of discussion, and sources of shared joy and refuge.

11:09 AM

|

Saturday, October 30, 2004

Ymmm...PIZZA TONIGHT

In a few minutes, two of our oldest friends are coming over for homemade pizza. We're looking forward to being together; when we met, almost twenty-five years ago, we were all just starting out in our various professions and our marriages. We met professionally, actually - the person who introduced J. and me was working for the same company as B., and recommended us to do design and advertising work for him. B. and T. got married the next year, and our relationships continued thorough the births of their three children, the rise and eventual demise of that company, more professional ups and down, house renovations, illnesses and deaths of parents, surgeries, politics, lots of birthdays, tough times and high points, confidences and complaints, children's graduations...it's the sort of friendship where any one of us is willing to shed tears in front of the others, and has, and also knows that the others will rejoice with us just as readily.

We don't see each other as much as we used to, when we worked together, but the friendship means a great deal to all of us, especially so, I think, because we knew each other before any of us had any money or even a career - we were just starting out, and it was all rather raw and honest, so there's nothing to hide, and no reason to impress. We just get together, and catch up, and enjoy a meal...

One connecting point has always been pizza. B. is Italian - really Italian - and he loves Italian food, especially pizza, which J. and T. both make at home. When times have been rough for business, there's always been our joke about opening a pizza joint together. Another connection is music - B. was a drummer in a rock band, way back when, and his career has always involved music peripherally, but his soul is thoroughly that of a musician and composer, which I hope one day he'll get back to.

I guess my archetypal image of the four of us is riding down the highway, laughing and singing at the top of our lungs along with some old song from the 60s or 70s, while B. plays the drums on the steering wheel, occasionally leaning over to hit an imaginary cymbal on my head. Good times.

5:50 PM

|

Friday, October 29, 2004

Duong Tuong Tran is a writer, poet and Vietnam’s most influential art critic. When meeting with writer William Zinsser and his wife in 1996, he mentioned that he had visited the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. and had written a poem there. The Zinssers were very moved by the poem, and it is included in William Zinsser’s new book, Writing About Your Life, published by Marlowe.

At the Vietnam Wall

by Duong Tuong Tran

because I never knew you

nor did you me

i come

because you left behind mother,

father and betrothed

and i wife and children

i come

because love is stronger than enmity

and can bridge oceans

i come

because you never return

and i do

i come

From the November 2 issue of The Christian Century.

1:47 PM

|

Thursday, October 28, 2004

UNPACKING WINDSOR

This link is to an excellent article, the best and most detailed-from-the-inside I've yet read, on how the Windsor Report might be read and interpreted from a western, progressive point of view. It's from the Anglican Journal, the official newsletter of the Anglican Church in Canada. The article includes interviews with Canon Alyson Barnett-Cowan, who served on the Lambeth Commission as Canada's representative, and with the new Canadian primate, Andrew Hutchison. It was especially helpful to me to read Canon Barnett-Cowan's answers, since she was able to speak first-hand to the intent of the Commission on various points.

7:11 PM

|

“How’s your book coming?” The question today from my father-in-law took me completely by surprise.

“Fine!” I said, gulping. “It’s going well.”

“Halfway?” he asked. I nodded. “Good for you!”

I told him I had just been there yesterday, to do another interview. He was surprised. “You’ve talked to him?” he said. “Really?” I don't know how he thought I was writing the book. I told him I had had a number of interviews and knew the bishop pretty well by now. He considered for a minute, then leaned forward, and said in a low voice, “I think I would be repulsed.”

“No, you wouldn’t,” I said. “He’s a wonderful man.” I thought about how the bishop had chattered with me in the tiny kitchen at Diocesan House yesterday, handing me a plate and a fork, sharing the sponge so we could both wipe up the salad dressing we’d spilled, how he’d insisted on carrying our empty plates back to the kitchen after lunch on our laps in his office – how humble and funny he was, how eminently likeable.

My father-in-law shook his head, but was smiling, as if he might just barely take my word for it. He wanted to know what had happened with the controversy in the Anglican Church; he thought it had all died down. We told him about the African bishops and their unlikely alliance with conservative Episcopalians, mostly from the south.

“It’s a cultural thing for me,” he explained. “There are lots of homosexuals in the Middle East,” he said, “but nobody ever talks about it. It’s just not something you discuss. And I’ve had lots of friends who were. But as priests?” Years ago, my father-in-law had staunchly defended someone in a small New England town who was known to be gay and had been persecuted and shunned; he’d been in academic situations where there were many gay teachers and students, and as far as I knew, had been very tolerant. This was something that was more about a visceral reaction to the gay person in his or her role as priest.

“How did you feel about women being ordained, back in the ‘70s?” I asked. I had to put the questions several ways before he could hear what I was saying.

“I can’t see a woman being a priest either,” he said. “And that was the final cleavage between the Anglicans and Catholics – when you began ordaining women.”

“Well, the Catholics have finally allowed girl acolytes,” I said.

“Wow!" he said, surprised. "That’s really a concession! Well - that's the first step downt he road..."

As annoying as his attitudes were, I was enjoying his honesty – we hadn’t talked about this before, certainly not so bluntly. That’s happening more and more these days; the guard is down.

“You see, where I am from, the priests are from the top intellectual segment of society. They are thinkers. The minister in our church was a member of the Arab Literary Academy! Intellectuals! And I just couldn’t see a woman being in that company.”

Ah, closer and closer to the truth. I felt J. tense up. He was taking pictures of his father while we talked; probably being behind the camera kept him from exploding.

"Really?" I pressed. "None of them?"

"Of course, there were a few. My own mother attended the first Arab Women's Conference! It was a big thing! And she read. But - she was a housewife." I felt a wave of sympathy for those women, and did a quick mental comparison of the lives of his mother and my grandmother, or even great-grandmother, who had been college educated and determined feminists even before that was a common word.

“How do you feel about women being ministers now?” (My father-in-law was a minister himself.)

“I don’t like it!” he said, laughing. “I just can’t see them in that…role.”

“Do you think they do a good job?”

“Not particularly!”

OK, I thought, at least we’ve laid that out on the table.

“Can you imagine a woman pope?” he said, and we both laughed.

“I can’t imagine a woman wanting to be pope!” I said.

“Certainly not like the current one!” he said. “Awful!”

Somewhere along the line, I’ve learned that these sweeping statements about women don’t necessarily include me, or his own daughter, although to some extent we’re all tarred with the same brush. My father-in-law only waxes poetic when talking about women as mothers: he has a Madonna complex, I think, and always says the same thing: “She looked so beautiful with her children! So lovely! So fulfilled!”

Sometimes I’ve bristled, or been wounded. But today I was just interested, because these attitudes are a window for me into a world we don’t see clearly at all from the West. His ideas were formed early in the last century, just when westerners began to be a presence in his homeland, today's Syria. Despite its origins next door, in Palestine, Christianity was seen as the religion of the West. Arabs who wanted to “move up” tried to emulate western ways, to give their children a western education, to learn English and French – and many of them became Christian, influenced by those first westerners who stayed in the Middle East to set up schools and hospitals. In Damascus, these were Presbyterian missionaries. Christianity was 600 years older than Islam, but in many ways it was overlaid on a predominantly Islamic society when the missionaries came and made converts. My mother-in-law, an emancipated, educated, self-made woman from the earliest country to establish the Orthodox church, Armenia, wanted her own career and independence. She had fought all her life against the traditional roles, and even though my father-in-law had defended her right to an education, equal treatment and good pay, the roles of men and women, both inside and outside the house, had been a constant bone of contention between them, as had his dismissive opinion about women's intellectual gifts.

All this made me think today of the situation in Africa, and how starkly different the expression of a religion can be, depending on its cultural context. The BBC reported the bluntest statement from the African bishops I’ve yet read, from the current meeting of 300 African primates in Nigeria: “Anglican leaders in Africa said if they condoned homosexuality - which is criminalised in the majority of African countries - then Africans would leave the Church or turn to Islam.” (italics mine)

The Nigerian president, Mr. Olusegun Obasanjo, who is a born-again Christian, “told the bishops he had followed ‘with keen interest your principled stand against the totally unacceptable tendency towards same-sex marriages and homosexual practice. Such a tendency is clearly un-Biblical, unnatural and definitely un-African,’ he said.”

Many of us in the west may find such opinions retrograde, but it’s so naïve – and unfortunately so typical of us - to think we can simply overlay our culture, and whatever historical processes it has gone through so far (whether toward "democracy" or modern attitudes about women or homosexuals) on someone else’s, or begin a dialogue only from where we are. Some of my father-in-law’s attitudes, formed nearly a century ago, clearly never caught up with those of his adopted culture. While I may deplore that, the best I can do may be to exemplify something else.

10:02 AM

|

Wednesday, October 27, 2004

No, friends, I have not dropped off the face of the earth - just been busy with traveling and work (and distracted two evenings in a row by our Icelandic neighbors, for whom the sun never sets and a 10:00 pm party is just the beginning!) There is something enchanting about explaining baseball to people who are totally baffled by not only the game but its mythical qualities (which, as Icelanders, they are quick to pick up on); and we've been talking about different cultures' children's stories; and then when that conversation wanes, there is always politics...or another bottle of wine.

We drove back down here on Monday evening, through the darkness of the forested mountains, where nary a light from a dwelling can be seen for miles at times. I was knitting, in the silver light of the nearly-full moon which led us over the frosty high pass and down into the village-dotted valleys. We had brought vegetables, bread, cheese, and we carried our packages and clothes and computers into the house just before the phone rang with a dinner invitation from next-door. The next morning I got up early and drove to Concord for my meeting with the bishop, who was in fine spirits and who I'll write about soon....

9:41 AM

|

Saturday, October 23, 2004

Thank you to the commenters on yesterday's post; I'd like to draw people's attention especially to the posts that Jake suggests; they are very good. I think I need to clarify something, while the discussion goes on: if the American church were to backtrack AT ALL on its positions vis-a-vis homosexuality, inclusiveness, or ordination, all bets are off, as far as I'm concerned. My remarks about reconciliation assume that Griswold and the Episcopal church are going to remain steadfast, and to slowly and gracefully move forward. I think this is what Rowan Williams assumes as well, and I think we can be fairly sure that he supports that in his heart, for what it's worth.

I have learned from experience that reconciliation takes two. If the fundamentalists refuse to maintain a dialogue, or to remain in communion with us, there is no way that we can force them. This has been the path even in New Hampshire, where our bishop offered the one dissenting church everything they asked for, including pastoral oversight by a conservative bishop - it was still not enough, and they walked out, leaving their keys to the church on the table. Their bottom line was "repentance", admission of "sin", and the bishop stepping down. This is, to those of us who believe in God's love for all humanity, unacceptable.

What distresses me about the current dialogue is the readiness to divorce that seems to be coming from both sides. I expect it from the conservatives. But I expect better from the liberals.

If we go down that road, we will end up with partitions and walls, entrenched ideologies, and self-righteousness triumphalism that is, at its heart, lonely and partial. In our hearts, I think we know this. There is such a tendency in the world today toward the black and the white, toward separation into "red" and "blue" America, into those who are "for us" or "against us", into the Muslim world and the Christian world, into Jew and Palestinian, Hindu and Muslim, fundamentalist and progressive...however we divide ourselves. We speak about "the price of unity", and this of course must be considered. In the present conflicts over homosexuality, for example, what is the price of splitting for the African churches who are struggling with the AIDS epidemic, if they are cut off from funding from the western world? What is the price to gay people? What price is any one of us willing to pay either for clinging to our ideologies, or waiting for justice? It is quite a serious question, and I certainly don't have the answer.

In my personal life, I divorced once, because it was completely clear to me that there was nothing to be gained for either of us by continuing; we needed to be set free. My present marriage has endured for 25 years, not without conflict, because being together was always a greater good than being apart. That doesn't mean it's been easy, and the greatest requirements have been patience, and a willingness to stay at the table.

I don't know what the future of the Anglican Communion is, or should be, but I do know that when people stop talking, you might as well say goodbye to hope, because it is over. In a world like ours, where this is increasingly the choice we make, every breakdown of communication feels to me like a further blow to my sense of what God asks of us in saying "love one another". If Gene Robinson, who has endured more than anyone else at the eye of this storm, can say he is willing to stay at the table and seek reconciliation, then so can I.

6:34 PM

|

Friday, October 22, 2004

Windsor Report, part 3: Unity, Truth, and Love

For someone who dislikes conflict as much as I do, to be reading the barbs being flung in both directions by so-called Christians over the Windsor Report, and trying - having - to write about it, is enough to make me curl up miserably under the bedcovers. Nobody in the opposing camps got what they wanted - and what a tragedy that was, for now both sides can continue to act like children. Yesterday and today I've read rants from conservatives who were outraged that the report didn't set up a new Province and throw out the liberals. Meanwhile the liberals are busy ridiculing the conservatives and complaining about the lack of courage shown by the Anglican commission in not standing up strongly for gay ordination. Interestingly, and not surprisingly, both extremes keep saying exactly the same thing: the report puts "unity" over "truth".

Doesn't all of this miss the point? Forgetting for a moment our opinions about whether the Anglican Communion is an outmoded institution or not, the Eames Commission was charged with the unenviable, but quite relevant, task of studying how a group of people worldwide might continue to live together despite our differences. It was not charged with delivering a "verdict" for one side or the other, nor could it do that and fulfill its original charge. Isn't this conflict over the rightness or wrongness of different ideologies, most of which are actually cultural, rather than theological at heart, exactly the same as what we see played out in countless venues across our world? Can't we look a little deeper?

Let's take a deep breath, substitute "love" for "unity" and see where we are. Can we say that love is ever more important than truth? I can, and I am a great lover and seeker of truth. The point the bishops were trying to make, and which I have encountered again and again in most of the moderate to liberal-but-not-strident leaders of the church, is that agreement right now on such a volatile issue is simply not possible. But does that mean yet another division, another wall, another self-righteous and permanent separation into we-and-they? If we look at the nuance behind the Report, we can see that what they suggest, and what is required is patience, continued talking, forbearance, greater attempts to understand one another, and an increased emphasis on working together on the other, much more pressing needs of our world that religion, at its best, is called to address. It seems to me that this is the real message of the Gospel, as well as the difficult, fractured times we live in, and it pains me that so many good people are so squarely in the "my way or no way" camp.

The Windsor Report suggested - did not "order" - concessions from both sides, trying to rein in the most flagrant and most destructive behavior. I'm quite sure it was clear to the authors that the American and Canadian churches are unlikely to stop moving forward toward the full inclusion of gay people, and that the conservatives would not stop their ultimatums about schism, but it also was clear to the commission that something greater is at stake - and that thing is not merely the preservation of the Anglican Communion, which could, frankly, be seen as a secular concept. What’s at stake is the model of love and forbearance, in spite of difference, that is at the heart of Jesus’ teaching, and which is so desperately needed in our world.

We are all asked to break bread together, figuratively and literally, week after week. When you actually do that, throughout a lifetime, with real and wonderful and annoying, even infuriating people, it changes you. This is what “staying in communion” means. It is not an abstract idea, it is a practice.

I saw the same arguments played out in my own parish, over similar issues, and although I was on the side of the progressives, I tried very hard to listen to the conservative point of view, and particularly to the pain of the people in the middle who just wanted to worship and to work on outreach or youth ministry or care for the sick. As much as anyone, I am concerned about justice and equality for all people, but I cannot believe that the point of the Gospel teachings is for one side to crush the other and then triumph over their victory; it is to learn to live together. We need to continually ask the question: is my attitude leading me closer to loving all people as God loves us, or further away from embodying that kind of love?

Recently a friend sent me this quote from Archbishop Desmond Tutu's 2004 book, God Has a Dream. I found it helpful:

"The endless divisions we create between us and that we live and die for - whether they are our religions, our ethnic groups, our nationalities - are so totally irrelevant to God. God just wants us to love each other. Many, however, say that some kinds of love are better than others, condemning the love of gays and lesbians. But whether a man loves a woman or another man, or a woman loves a man or another woman, to God it is all love, and God smiles whenever we recognize our need for one another."

One of the lessons of my adult life is that I now know that I have great need of people who differ from me. I don't want to be surrounded only by people who think like me, act like me, look like me, because that means I will not be challenged to grow and change. And when I pay close attention, I recognize that the times when I have been transformed by that universal love which I call "God" are not when surrounded by friends who it is easy to love and understand, but in the unexpected and miraculous moments of closeness that transcend profound difference, where nothing is supporting the connection but an invisible hand.

8:05 PM

|

Thursday, October 21, 2004

Parc la Fontaine, Montreal, two days ago

Windsor Report, part (2)

While there are many parallels in language and style of attack, personally I’m not so sure about how the ordination of gays and lesbians will play out compared to that of women. (It should be noted that we're talking mainly about bishops; openly gay men and women have been ordained as priests in our denomination for some time now and are serving in many parishes, although there is still resistance and prejudice.) The reactions are so much more visceral in the case of homosexuality, and easier to maintain: one can shut oneself off from relationship with homosexual persons for a lifetime, if that is what one chooses, but very few people are able to do that with women. In practically every household in the world, men and women have to try to get along with each other. Certainly they do it in different ways, based on cultural mores and expectations, but women worldwide have not stayed still or passive; there is hardly a place on earth where women have not begun to press for greater equality in all areas of life, and the right to be seen not as embodying shame or sin, but as equal human beings in the eyes of God. It is no longer possible to shield women anywhere from knowing about the rights and freedoms enjoyed by others, and the desire of human beings is always toward freedom, and against oppression. No wonder knowledge and education are so dangerous. If one’s wife - whether in Alabama or Iran or India or Saudi Arabia - doesn’t press for equality and fairness, probably one’s daughter will. Rebellion and persistence among one’s closest relations has a way of eventually wearing down stereotypes and resistance, and forcing reconsideration.

So sexism, probably because it involves fifty percent of the human race, is gradually breaking down. Racism and ethnic conflict persist largely because people are able to wall themselves off from those who are different from themselves, and governments and institutions everywhere, including religion, contribute to those walls (which are in some cases even literal) and divisions.

Hetereosexism will continue to persist because separation is possible and even seen as desirable. Like racism, heterosexism can exist in society and in the church long after gays and lesbians are “accepted” or even given equal rights, if people fail to enter into genuine relationships with those they consider to be “other”. While claiming a desire for unity, the conservatives in the church continue to use contamination language with regard to homosexuals and those who support them, refusing to sit in the same room with Gene Robinson and his supporters, to stay in the same hotel at the meetings of the House of Bishops, or to share Communion, the most central sacrament and symbol – “breaking bread” – of common life together? For the most conservative, one reason that has been given (since this practice of exclusion for some originated with the ordination of women) is that they cannot share the Eucharist because the bread may have been touched by a woman priest. Clearly that fear is extended to “contamination” by homosexual priests as well.

The fact, therefore, that the Episcopal Church has decided to opt for openness and inclusivity is a major problem for those who refuse to change. Openness requires discussion both of sexuality and of honesty: is it moral, for example, to allow gay bishops who are closeted, while banning those who are open about their orientation? And inclusivity is deeply problematic not only because it forces relationship in the same way that racial integration did, saying that all people are fully human in the eyes of God, and entitled to full participation in the life of the Church, but because it calls us to go deeper into the meaning of loving one’s neighbor that is the central message of Jesus’s life and teaching.

Tomorrow, more on “unity vs. truth”

9:22 AM

|

Wednesday, October 20, 2004

MORE on "The Ambience of Words"

An enormous merci to Language Hat for quoting my final post about my father-in-law and initiating a most interesting thread of comments on Arabic pronunciation, al-Mutanabbi, and other diverse topics. Please read the comments; they're fascinating.

7:51 PM

|

Tuesday, October 19, 2004

I've been following the release of the Windsor Report by the Eames Commission, a study group appointed by the Archbishop of Canterbury to try to offer recommendations about how we might preserve the unity of the Anglican communion despite major theological differences worldwide. Bishop Eames is Primate of All Ireland (how's that for a title!) and was the chairman of a similar commission appointed in the wake of the first women's ordinations back in the mid-1970s.

I've also been monitoring the initial reactions to the report; all this is important to my book and I'm trying both to figure out what exactly the report says, and how it will be acted upon - or not - by both sides in the conflict. Over the next few days I'll post some of my first thoughts about this; it's helping me to try to write them down in some sort of coherent fashion, so I hope even those of you who find all of this tedious and irrelevant will bear with me.

Meanwhile - I had a good experience at the Canadian eye doctor's today, and managed to negotiate the purchase of new glasses with a retailer who didn't speak any English at all; she and I liked each other and ended up quite amused. The other exciting event today was my first purchase of a whole fish, which I managed to fillet and cook, and it was delicious. I had no idea what happens when you buy a whole fish; I figured they just hand it to you. Well, they ask you what you want done with it. I said "couper la tete", and they asked "grater", which I gathered means "scaled". I said yes. When I got home and looked, I had a fish that had been cleaned and scaled, but still had its head. Being a former fisherman, I managed. A whole new world of fish cookery has just opened up.

But now, back to the so-called "fishers of men":

Yesterday at noon, the long-awaited report and recommendations on the issue of homosexuality and the Anglican Communion were released at Lambeth, England. The “Windsor Report”, whose conclusions have been speculated upon a great deal in the press - even two days ago the Washington Post and the London Times offered widely diverging predictions about what would be revealed– in the end came down on the side of unity and eventual reconciliation.

It calls on the American Episcopal Church to apologize for its consecration of an openly gay bishop, and for a moratorium on consecrations of other gay bishops and blessings of same-sex unions. The report chastises both the Episcopal Church and the Canadian Church (British Columbia has been allowing the optional blessing of same-sex unions by parishes who wish to do so) for caring more about their own paths and their own theological interpretations than the “interdependence of the Anglican communion” and the “need for unity”. It asks the Episcopal Church and the bishops who participated in the consecration of Gene Robinson to issue a statement explaining their reasoning, and says that the statement “must be based on Scripture”. What the Report does not do is to recommend harsher “punishment”, such as the most conservative Anglican bishops in Africa, Asia, and the United States have called for, such as a reversal of Gene Robinson’s consecration, outright “excommunication” for the American or Canadian Churches, or, particularly, establishment of an alternative North American Province by the Archbishop of Canterbury in which the conservatives who want to break with the Episcopal church could have their own interpretations and their own bishops. The report also chastised those conservatives who have tried to set up alternative structures and forms, such as the “flying bishops” scheme in which conservative, often retired, bishops from other dioceses and from abroad come into US dioceses to perform major functions, such as confirmation, as a protest against the oversight of the diocese’s legally elected bishops who are more liberal. One of the bishops who has participated in these actions is, interestingly enough, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, who recently performed confirmations in the Diocese of Virginia; hr is much mroe conservaative than the current A of C, Rowan Williams. One further recommendation is that all the churches in the Communion sign a "core covenant" stating the core beliefs.

I was surprised, frankly, that the report (which was unanimous among the Commission members, who included some very conservative voices) was as measured as it turned out to be. It’s a very long document, some 100 pages, and I certainly haven’t read all of it. In striving to preserve unity, the report will probably please those who don’t want to split the Communion and who are willing to allow, as is the traditional Anglican way, for wide variations in scriptural interpretation and theological opinion. But from my experience, listening to and watching the conservatives, I doubt that they will accept these recommendations or be satisfied with a slap on the wrist and an apology: nothing short of an about-face and “repentance” will satisfy them. The initial reactions bear this out: conservative church groups in Britain and the US have called it “toothless”. On the other side of the issues, the Americans and Canadians have already said they regret the problems their actions have caused, but that they will continue as they have been. I doubt very much that the "core covenant" idea will be acceptable to the progressives, either.

As the Report notes, we still have areas of the Anglican Communion which refuse to allow women to be ordained while others have moved on from that issue decades ago; but while there is “impaired communion” over the ordination of women, the dire predictions of schism over that issue have not in fact been borne out. Implied in the recommendations, it seems to me, is the hope that in time the same thing will be true over the issue of homosexuality, and that we can limp along together without any consensus. It buys time, and calls for patience.

More tomorrow on what makes the issue of homosexuality so volatile.

9:39 PM

|

Monday, October 18, 2004

LES YEUX

I've spent most of today working on the report released at noon by the Eames Commission with its recommendations for the future unity of the Anglican Communion around the issue of gay bishop ordinations and the blessings of same-sex unions. It's actually interesting to be doing that from Canada, since the Canadian church was also chastised in the report, and there's been quite a lot on the radio about that. Tomorrow I'll start posting about this, but I thought today maybe it would be nice to just have a picture - like this one of the blue eyes on rue Gilford, near Papineau, whose gaze stopped me yesterday as I rode by.

9:06 PM

|

Saturday, October 16, 2004

This is the final installment in a five-part series about my father-in-law.

5. The Ambience of Words

“I may have a new Arabic student,” my father-in-law told us, after dinner. “It’s a woman. She called up other day and said she had heard that I teach. She’s coming next week.” He has one regular student who studies with him each Wednesday, and another student who is “on leave”: he’s a minister who is currently in the Sudan doing relief work.

“Grandpa, how would you explain to someone how to pronounce an ‘ayn’?” M. asked. “Is it different than a glottal stop in Hebrew?

“Oh yes,” he said, “In Arabic you have to open your throat and…” he demonstrated, and asked her to repeat; he demonstrated again, a little smugly; he loves being able to do things that are difficult for us.

M. came into the kitchen where I was cleaning up, frustrated but amused at all the camel-noises they’d been making. An “ayn” appears in the middle of her last name. “Oh, it’s nothing, she whispered, “I’m just trying to learn the right way to pronounce our own freaking name.”

Up until two years ago, my father-in-law was still preaching and conducting services – weddings, memorials - and filling in in the summer for local Unitarian congregations. He was an enormously gifted preacher and public speaker who never spoke from anything but a few notes written on index cards. One Monday he told us, “I lost my train of thought yesterday. I really got mixed up. I don’t think they knew it, but it’s never happened before. It’s time to stop.”

We went with him to his last engagement, in a small, wealthy, rural Vermont town where he had been filling in for a month. He told the congregation it was his last sermon, and preached well, although we could tell he was struggling a bit with his emotions. Although a few of those present had known him for many years, most of them couldn’t have known what an occasion that really was. And few of them, too, knew anything of the journey of his life, from his childhood in Damascus, Syria, listening to folk stories and poetry under the rooftop grapevines of the family house, to preaching in this white upper-crusty, old-money conclave of northern New England.

In his later years he seemed to try to recapture that remembered ambience. His balcony was covered with flowering plants, and he loved to sit there, cracking pumpkin seeds in his teeth, watching his beloved hummingbirds. He grew parsley and green onions for taboulleh, radishes for their hot leaves, tomatoes for their color; and rose geraniums for their scent. Inside the apartment, he read Arabic literature and poetry, and kept up with the press so that he could discuss his favorite subjects: foreign affairs and Middle Eastern politics. I’d watch him during our discussions, as he inveighed against Bush and Blair, incredulous that this man had been born during the Ottoman Empire. As a child in Damascus, he remembers seeing Lawrence of Arabia ride into the city; his grandfather had been present at that famous meeting Lawrence had with the Arab elders and tribal leaders before the Western powers intervened and began to change the map of the Middle East.

An avowed intellectual who keeps a small statue of Socrates next to his chair, he believes that the highest profession is that of philosopher-poet, surrounded by disciples and students, eschewing the needs of the flesh except for food, ideally provided by uncomplaining, attractive wives, daughters, and daughters-in-law. There are many inconsistencies. He’s always been disdainful of games, of sports, of organized leisure, while praising “honest work; in his parlance, “decent” ( as in “they’re very decent people”) is synonymous with “simple and hardworking” and it is both praise and put-down. He holds rather Tolstoyian notions about farming and gardening; the family could barely keep themselves together one Sunday when he waxed eloquent in his sermon about the joys of working in his vegetable garden, which he had gotten other people to plant, weed, harvest and cook from; his pleasure was in “inspecting” it several times each day. Physically he has always been given to frequent napping, and a habit of dropping books, papers and clothes in piles next to his chairs where they lie until someone else picks them up. At 88, he decided to mow his lawn for the first time in his life “just to see what it felt like”. He borrowed a push mower from his brother, took it for two passes across the lawn, and felt the chest pains that precipitated his bypass surgery a week later.

From his armchair, though, and the bed which he says is "heaven", he now conjures the scents and sights and sounds of his youth, and is never happier than when we draw him out and ask him for his memories. He’s spotty about certain recent events and people, but his long-term memory is nearly flawless, and it includes huge quantities of Arabic verse, as well as songs and hymns, that he must have learned by heart seventy, eighty, even ninety years ago. This ability to recite is one manifestation of the vast difference in cultures and time that he's traveled: he grew up in a culture still based on oral tradition and memorization of texts, most notably the Qu'ran. In Christian circles like my father-in-law's family, people memorized and recited scriptural passages, hymns, and the great works of Arab poetry, as well as fables and proverbs.

“How do you begin teaching Arabic to someone?” M. asked. She has studied more of the language than any of us, and readily testifies to how difficult it is.

“I begin by trying to explain the ambience of the words,” he said. We all looked perplexed. “You see,” he said, “every word in Arabic is surrounded by meaning; it refers to a whole constellation of experiences that are particular to that world, to that way of life…All of that is contained within the language.”

“Take the word ‘happiness’,” M. said.

“What is happiness to an Arab?” he countered. “That is where you have to start. You have to see the desert, smell the bougainvillea…” He shut his eyes and began to recite two couplets in Arabic; it was beautiful.

“al Moutanabbi,” he said, opening his eyes. He raised his hand and punctuated each noun in the air as he translated:

Horses, and nights, and the desert know me –

and the sword, the spear, paper, and the pen.

“Wonderful!” He shook his head, smiling with pleasure. “He was quite the fellow. A great poet, and a warrior too. His caravan was attacked by bandits and he was going to flee, but one of his companions reminded him of these lines he had written, and challenged him.” He growled, shaking the words like a rabbit in the jaws of a wolf: “‘Aren’t you also a fighter who praised the sword and the spear?’ So he rode into the battle – and was killed.” He grinned, and shrugged: c'est la vie.

He shut his eyes and recited the Arabic again. I watched the bones of his thinning face move as he spoke; his voice was a strong as ever, and his silken white hair curled at the back of his neck. The three of us exchanged astonished glances. For us, the remarkable moment was becoming fixed in time and space and memory - but he was flying, gone somewhere we'd never been.

7:37 PM

|

Thursday, October 14, 2004

This is part four of a series of posts about my 95-year-old father-in-law.

4. Of Books and Authors

“Don’t mention my book to him,” I told M. as we were getting ready to leave our house that evening. She and I had just spent much of the afternoon “talking writing”, down to the nitty-gritty of paragraphs that she plucked out of my manuscript as she so generously read it.

“Why not?” she asked.

“He doesn’t approve of the subject,” I said.

“You’re kidding!”

“No, really. He thinks it’s awful, so I don’t talk about it. I don’t think he knows I’m writing it, although some of his friends at the home know, because they're Episcopalians. We can talk about your book instead.” She raised her eyebrows, but we left it at that.

When my father-in-law retired from his long career as a teacher of Arabic and Middle Eastern studies, he continued his work as a minister but devoted himself more and more to writing. During the next two decades, starting about when I first met him, he wrote three full-length books: a life of Jesus, of Moses, and of Mohammad. They were all “creative non-fiction”, and written in a style somewhere between the flowery prose of a native Arabic storyteller, and a scholarly work of theology. And they were creative and decidedly unconventional, rather than religious, based on his extensive knowledge of the Middle East and his imaginative speculations about what the "real" life of these figures - all of whom he admires irrevently but ardently - might have been like. As a result, neither the popular book market nor the religious press would touch them. This was the greatest disappointment of my father-in-law’s life. For one thing, he didn't understand how the publishing market worked in the modern western world, nor would he listen to the advice of editors, agents, other writers. He had expected, I think, to make a big splash once he finally wrote down the ideas that had regaled generations of adoring pupils and Unitarian parishioners, but it wasn’t to be. He kept writing until he was 92 or so, and to this day, his dream is to get his major works published – but he is generous enough to want others to be successful, especially his granddaughter.

Before dinner, he grilled her about her work. How was it going? Did she work on her writing everyday? How was she supporting herself? She surreptitiously rolled her eyes at us before telling him that she had some free-lance writing work that paid the bills; sensing that more information was needed, she even told him how much she charged per hour. Later that evening she said she hadn’t known what to say: “He thinks I’m irresponsible, doesn’t he? So I told him I had free-lance work that pays a lot – he doesn’t know I’ve only billed one week's worth all year!”

“Great!” he said. “That’s a lot per hour! So you must be doing all right.” M. shot us a helpless glance. “And your writing is going well.”

“It really is. I think I’m actually going to finish it, finally.”

“Terr-ific! I always thought we had a book in the family.”

“Beth has a book.” Oh-oh. M. screwed up her face in apology. I waved my hand, signalling her it was all right.

“She is borrowed,” he said, affectionately but decisively. That was all right; it’s always been clear to me that in this family (and that generation) blood rules all: children are children, and the people they marry, no matter how much you might like them, are something else. “And besides,” he added, “she doesn’t talk to me about it. She thinks I don’t approve.” Another helpless glance from M. “But you will make us all proud,” he said to her.

She went into the study to retrieve the last pages of his manuscript. He turned to us and quietly pronounced his verdict, with a pleased face: “I think she’s really coming along.” I cut up an apple and two oranges and split each doughnut into four pieces, and put them all on a plate with a bunch of grapes. My father-in-law, who loves sweets but is rigorous about following his diet since he was diagnosed with diabetes, selected a couple of orange sections.

The manuscript that was printing was a long story (“It’s a novella, Grandpa”) written about ten years ago as a semi-autobiographical memoir and social commentary. He had “lost” it in his computer and my husband had “found” it for him the week before; he wanted to give it to another resident who had expressed interest. Our niece walked toward her grandfather, holding out the pages.

“Taib binte!” he said. “Good girl!”

6:25 PM

|

Wednesday, October 13, 2004

A NOTE IN-BETWEEN INSTALLMENTS

I spent a chunk of the afternoon, following lunch with my father-in-law (ohmigod - I had brought lunch, but he insisted we help him eat food out of his refrigerator - so far I haven't had to call 911), at the eye doctor. Now my pupils are recovering just enough so that I can see the screen.

I had been having more and more trouble with my contact lenses (I've worn contacts since 1974) and had consequently been wearing my glasses more frequently. Some of that was due to being in the city, where it's less trouble and more comfortable to wear glasses, but mostly due to all the computer work and long hours of writing. But the more I wore my glasses, the worse my vision got as my corneas changed shape back to "normal" - whatever that would be after all these years of lens wear. In fact it was so bad and my eyes hurt so much I was worried something else was wrong. But no - the doctor reassured me that there's no medical problem, just an optical one, including an astigmatism that the lenses had completely masked. And I got to see a fabulous computer map of my corneas, courtesy of a far-out corneal topography machine that I'd never been subjected to before...and listen to an entertaining Terry Gross interview with Howard Dean while my pupils dilated.

But it's back to glasses only for me, for quite a while: two new pairs, for distance and reading, until things settle down. Funny - it used to be a vanity issue for me. Now I'm just dying to be comfortable and able to work.

4:51 PM

|

Monday, October 11, 2004

RECOMMENDED READING

"Breaking Ranks", an article by David Goodman in Mother Jones in which U.S. soldiers speak out about the war in Iraq.

7:20 PM

|

3. A Train Ride

In the study, the printer began turning out pages. I said that dinner was ready, and everyone settled into a chair with their plates of food – the only “dining” table has been a repository for books, papers, mail, and photographs as long as my father-in-law has lived in his apartment; we didn’t even consider clearing it off. For a while nobody spoke; we were all hungry. “Does he like wara einab?” my father-in-law asked me, for the hundredth time, nodding in his son’s direction.

“Nooo,” I said.

He shook his head. ‘Does he like mujadarra?”

Again, no. But M. spoke up. “I love it, Grandpa. I eat it all the time.” He immediately brightened, and waved his fork in the air. “I love it!” he exclaimed. “For some reason that’s all I want to eat these days.” He made a face and growled: “They don’t know how to cook anything downstairs. It’s all tasteless and overcooked. I told them, ‘Why don’t you go to the Chinese restaurant and see how they cook vegetables?’ It doesn’t take a PhD. But did they do it? No.” A big shrug and another wave of the fork, dismissing the thought. “But mujadarra! Ah! I make it every few days and eat it with bread. It’s so wonderful! Have I told you the story about how I started to love mujadarra?”

“Yes,” I said, “You’ve told us, but probably M. hasn’t heard it.” In fact he tells us this story almost every week, in conjunction with telling us how he has lost his appetite and the food in the home is tasteless, but this time we heard not only the core but an embellished version around it. Mujadarra is a simple, peasant dish made of lentils and rice cooked together, with fried onions.

“When I was a boy I had been sent from Damascus to boarding school in Beirut, and as part of my studies, when I was about fifteen, I was sent by one of my teachers to a village near the border with Palestine.”

He was born in 1911, so this would have been about 1926.

My job was to teach some English to the children in that village. They were Shia Muslims, and the imam of the village refused to allow any girls to go to the school. So the boys were taught by the regular schoolmaster and the girls were taught privately by a woman missionary. I helped teach the boys. There was a beautiful crusader castle nearby, overlooking the sea, and I took them up to it and taught them about what it was and who the crusaders had been.”

J. and I had never heard any of this – neither the Shia part, nor the crusader castle part. This would have been in what is present-day southern Lebanon, where there has historically been a large Shia population. He may have been talking about Beaufort Castle, one of the most famous of the crusader castles, built in 1139 and largely destroyed by the retreating Israeli Occupying Forces in May, 2000, despite the pleas of the Lebanese prime minister.

Then when my teaching stint was over, I took the train back home to Damascus. I didn’t have any food, and I was very hungry. In the same car, across from me, was a peasant family – a woman and her three children. She took out a package and unwrapped it; it was their lunch, and it was mujadarra. Nothing had ever smelled so good! I watched them eat it, and I got hungrier and hungrier for mujadarra, but of course I couldn’t ask them for any.

When I got home my mother asked me, as she always did, what I’d like her to cook for me. I immediately said, “Mujadarra!” She was shocked, because mujadarra was the food of the poor – we didn’t eat it in our house. But I was insistent. “I’m dying for mujadarra!” I said. So she made it for me, and I’ve loved it ever since.

I only remember my Armenian mother-in-law, who also maintained a fairly aristocratic kitchen, making it once, and it was really delicious. But this peasant dish is what my father-in-law craves now.

A less classical spelling of the dish is megadarra. Claudia Roden, in her original Book of Middle Eastern Food (Penguin) writes:

"Here is a modern version of a medieval dish called mujadarra, described by al-Baghdadi as a dish of the poor, and still known as Esau’s favorite… In fact, it is such a great favorite that although it is said to be for misers, it is a compliment to serve it."

"An aunt of mine used to present it regularly to guests with the comment, ‘Excuse the food of the poor!’ – to which the unanimous reply always was, ‘Keep your food of kings and give us megadarra every day!’"

Next: Of Books and Authors

3:58 PM

|

Sunday, October 10, 2004

2. The Decoder Ring

Before we left our own house that evening, M. had said, “You have to help me. My whole history of coming to New England have been these visits where I always tried to do the right thing, but where it would become clear to me that I wasn’t doing the right thing. I always felt like there was some unwritten expectation about what a granddaughter was supposed to do, or how she was supposed to act, but it never got communicated to me. I was supposed to just know my role – but how? How was I supposed to find out? Even now, I have no idea. And it makes my stomach hurt to think about it.”

We laughed, ruefully. “Join the club,” J. said. “That’s the story of my life.”

J. and I have spent more hours discussing this than I can count. What we’ve come to realize is that it’s partly the story of being born into an immigrant family. There are so many unwritten cultural ways and expectations and roles that the parents have brought with them, but the children, growing up here, know nothing about. These things aren’t communicated by the parents or the surrounding native culture, since (as in this case) it may no longer be present, while at the same time the parents are encouraging their children to assimilate. When the native language isn’t taught, another potential key to unlocking the mysteries is unavailable. Yet, the parents continue to have values and expectations that were based on how they grew up. So what the children get are mixed messages, and feelings that, no matter what, they aren’t doing the right thing. What was the key? Where could they find the decoder ring?

It’s sometimes nearly impossible for the parents to articulate the gap, even when confronted. Only in recent years, by asking probing questions, and especially by becoming friends with people from the Middle East, have we begun to unlock the code, to translate the hieroglyphs. For example, my husband started wearing a beard when he was young. His parents, especially his father, hated it. At the time, my husband had thought it was because of the general distaste for “hippies”. But later on – much later – he learned that Muslims in the native country generally wore beards and Christians rarely did; it was one way to distinguish between the religions. His father admitted, only this year, that he had an instinctive reaction against beards because they were worn by the mullahs, and he had had some unhappy encounters, as a child, with mullahs. The time span between his unhappy encounters, and the explanation to my husband, was probably eighty years.

By the same token, these Christian parents had been raised in a society which was largely Muslim and they shared many of the same values and ideas. They had a lifelong aversion to alcohol, and criticized people who drank it. My mother-in-law rarely allowed her neck and arms to show, and was constantly commenting about the immodesty of young American women, to the point where I was careful about what I wore in her presence. My father-in-law astounded us by telling us, not long ago, that his mother always “covered” when she went out into the street – meaning that she wore a veil or scarf over her hair. “Everyone did in those days, Christians and Muslims,” he told us, shrugging. “It was just what you did.”

It was a revelation to finally understand, through knowing Muslim friends and coming to understand Islam much better, that many of my husband’s family’s values and reactions, which had seemed so incomprehensible to their young American children, had been shaped by their immersion in a Muslim society. In a rare moment of unguardedness, my father-in-law said, not entirely joking, “If you speak Arabic, you are Muslim.”

9:06 PM

|

Saturday, October 09, 2004

My next few posts will be a story about my father-in-law, in installments. This is part one.

1. Matters of the Heart

On Friday night, we took dinner to my father-in-law, so that we could sit and talk together as a family: his son, his granddaughter, and me. M., as I’ll call my niece (she is the daughter of J.’s considerably-older brother) and I had shopped in Montreal and brought back Arabic tidbits for the occasion: little meat-filled pastries; homemade hummus; wara einab (stuffed grape leaves); the wrinkled black Moroccan olives we all love; a special kind of pita spread with za’atar ( a lemony spice blend that is mostly ground sumac) and tomatoes. And we made rice pilaf with vermicelli and almonds, and green bean, beef and tomato stew - a particular family favorite.

My father-in-law was lying on his bed when we arrived. He got up laboriously, and slowly made his way out to the front room, groaning. I took the bags and pots and pans to the little condominium-size kitchen and began unpacking and heating things up. M. said, offering her arm, “Grandpa, let’s go out on your balcony and look at your plants. Show me what you’re growing.” J. helped me in the kitchen, as we peered through the pass-through at the scene out on the porch: the very aged grandfather, now seated on a chair, explaining each plant and its summer history to his nearly forty-year-old, youngest granddaughter. I saw a rare happiness and animation erase the pain in his back and legs; I watched M., being her dear self, trying to connect with this patriarch for what will surely be one of the last times. J. quietly reached for his camera. I turned to the stove, like generations of women before me, and for what was the first of many times that evening, my eyes filled with tears.

My father-in-law and niece came in from the balcony, and he settled into his favorite chair with a huge sigh: “Ahhh!” “Tell me,” he asked her, “can you print a copy of a manuscript for me on my computer?” This is the sort of thing he often asks any visitor who might be computer-savvy; we have learned from experience not to get too involved in his computer woes or risk being caught in a cycle of blaming and frustration fueled by near-total ignorance: something he reserves for his family. M., naive about this and eager to please, said “sure” and J. went to the study to try to help her with the aged computer.

My father-in-law got up after a bit and came to inspect the dinner and talk to me through the pass-through. “Do you have everything you need?” he asked. “There are plates in the --" he waved his arm toward the dish drainer -- "and more in the cupboard. I’m sorry, I can’t do anything these days.” I assured him that everything was under control, I was delighted to do it, to please let me wait on him. “I have no choice,” he said, laughing. “That’s the way it is!”

I asked if he had laban (yogurt), and he told me where it was in the refrigerator. “The stew smells delicious,” he said, running the “d-e-l” together as the first syllable, and saying “ISH” as the emphasized second syllable, almost like taking a bite of the savory word itself.

We could hear J. and M. talking as they worked in the far room. Then my father-in-law balanced on his cane with both hands, looked straight at me and said, “You know, I almost died last night.” I stopped working, picked up the towel and wiped my hands.

“What happened?” I asked, looking closely at him.

“I woke up in the middle of the night, and my chest was terribly constricted, painful, my arms were numb. It was as close to a heart attack as you can get, I think. And it’s the second time this week this has happened.” He laughed, self-consciously; I was thinking, “maybe closer than that.” He went on: “So I reached for one of those little white pills and put it under my tongue, said, 'all right, what will be will be,' and went back to sleep." I smiled, amazed by him as I often am. Then he laughed again, more genuinely this time. “But I woke up!” I laughed then, too. He told me that he had told the story to a friend of his there at the retirement home, a woman who is 91, and asked her if it happened again, could he call and ask her to come and witness it? “She said she’d be glad to,” he said. I peered at his face and thought his eyes looked misty.

“You can call us at any hour,” I said, emphatically, pleadingly. “We can be here in ten minutes!”

“I don’t want to call you in the middle of the night,” he said. “And besides, what can you do? When it happens, it’s going to happen.” Then his attention shifted. “I have fruit,” he said. “And cakes – there are some of those little cakes.” On the corner by the sink was a plate with three doughnuts, pilfered from the breakfast buffet downstairs, no doubt. One had already been broken and nibbled by my husband. “Great,” I said, “that can be dessert.”

Next: A train ride

2:07 PM

|

Wednesday, October 06, 2004

We left the city at 6:30 and drove through the Green Mountains, where frost covered the north-facing slopes and the fall color - not spectacular this year, except for the occasional brilliant red tree - is marching inexorably southward. A cheerful young woman with long, wavy blond hair checked our passports at the U.S. border. After the requisite questions about where we lived and whether we had exotic fruit, beef, or firearms in the car, she asked, "And what is your profession, sir?" "Photographer and designer." "And what do you do?" she asked, looking at me. "I'm a writer." "And you?" She leaned out of the booth to address our niece in the back seat. "I'm a writer too." 'Well, guys," the customs officer said, reshuffling our passports and handing them back with a smile and a little nod, "a photographer, writer, and writer. OK! Have a nice day!" I guess that means she figures no taxes are due from our high-paying secret jobs in Canada!

By 11:30 we were unpacked, somewhat cleaned up, and at the retirement home for lunch with my father-in-law. Our niece (his granddaughter) told him about an essay she had written about studying Arabic in a community class. He was intrigued - it is his language and his love, after all, and none of us speak it - and asked her some questions, and then said, "So - it's not really about studying Arabic, it's about the people in the class who were studying Arabic." "Yes," she said. "That's it."

After lunch we went up to his room. "I can't do anything," he said, handing me the latest New Yorker which he had just picked up in the noontime mail.

"No, you'll read it," I said, looking with despair at the cover - an excellent encapsulation of the nation's electoral identity crisis: Bush in fatigues, leaning familiarly on his lectern with a wise-guy, conspiratorial grin on his face, and a golf club over his shoulder, and Kerry in officer's dress whites, hands behind his back, looking down his patrician, educated nose, aghast, at the lowly private.

"No, there's nothing in it I want to read anymore. Too much gossip. But take the New York Review, I've read all of it. Some very good things - an article on Iraq by that fellow at Harvard..." He settled back into his chair and sighed. "I get up every day full of ideas and things I want to accomplish, and at the end of the day I haven't done a single one of them. This is what old age is!" He threw up his arms in a gesture of futility, and smiled, throwing off ten or twenty years. "Oh well! I sleep beautifully, and when I'm lying in bed, there isn't an ache or pain! It's heaven!"

On the way back to the car our niece said, "He's a lot smaller." We walked in silence for a while, and then she spoke again. "But he sure is sharp. He picked up right away what I was doing in that essay! It took me weeks to figure that out!"

4:46 PM

|

Tuesday, October 05, 2004

Here, we can only go to Little Italy (a great pleasure in itself) but it has been such a delight to read Ernesto's recent posts from the Rome. And he's now in Paris...I am so happy for him!

--

Tomorrow morning, early, we're heading back south. How the time speeds by! The biweekly schedule may make it seem faster; the seasons leap-frog forward, change seems to happen twice as fast, from progress on construction projects to the buttoning-up of the city in preparation for winter. Today I cycled downtown to meet our niece in Chinatown for a dim-sum lunch, and nearly froze: I'll be bringing my gloves back next time, but I found that my black wool beret, if pulled down over my ears, fits neatly underneath my bicycle helmet. How welcome was the hot pot of jasmine tea, the slippery shrimp-filled noodles, the delicate fish-stuffed steamed dumplings! How delightful the crunch of whole, deep-fried, lightly battered prawns!

Au revoir, wonderful city. I leave with a few new pounds of books in my duffle and, if words could be weighed, my laptop would contain a gain commensurate with that caused by the fromage et beurre in other, more obvious parts!

6:13 PM

|

Monday, October 04, 2004

After a long day of work, I walked into the park at dusk. The day had turned stormy, and as I crossed the sidewalk the trees tossed their red and yellow leaves in the wind, scattering more onto the wet pavement. In the west, the sky was still bright, and a single golden cloud swept across the blue window between the two lines of dark trees, as if it had sails.

Under the dark, tall trees, the wading pools and swings were abandoned and silent. A patch of acid-yellow marigolds under the shrubbery glowed in the raking light. I stood for a long time beneath the line of huge old poplars, listening to the wind roaring in their leaves: the sound of a waterfall.

The stadium lights were on over the empty emerald ballfields, but except for a few joggers and an old, thin man in a running suit, walking far faster than his age, the park was nearly empty. Three friends played boules on the graveled court; a cyclist in black sped past, going home. A man in a raincoat stood alone, staring out through the trees. I stopped by some wet, green park benches where red maple leaves had stuck in the earlier downpour, and took some pictures under a grove of younger trees, resting my camera on the top of one bench in the failing light.

Behind me, the setting sun suddenly turned the sky red, and every reflective surface took on a strange sheen of dark rose. In the upper lake, the fountain was off, and the water being drained, forming discreet pools in the raked gravel of the bottom. A duck quacked somewhere in the weeds along the far edge, and a man with a long stick walked slowly in what used to be the lake edge, fishing for – what? pennies? just beneath the surface. I was getting cold; the wind picked up; I wished for my black wool beret for the first time this season, and walked hurriedly out of the park, toward home.

9:59 PM

|

Saturday, October 02, 2004

The flatness defined by corn in the south is concrete to the north and west of the city. We drove there today, through the grey horizontal industrialized zones, leaving behind even the green oxidized steeples of the Catholic churches that punctuate the sky in every direction, to pick up our niece who was flying into Trudeau airport (formerly Dorval) from L.A.

The airport was smaller than we'd expected, and large parts of it are under construction or being renovated; still, it is an international airport with large planes arriving and departing. Not once, during the hour we were there, did we hear an announcement of any kind. Other than the fact that there was no observation deck or area from which you could watch the planes, there were no heightened security measures: no signs for unattended baggage or suspicious packages, no police or security guards in the non-passenger areas. It felt like... a time warp.

This is a rare rainy day; although it's been a very wet summer in Vermont, theres been a lot less rain up here. In the afternoon we went up on the roof to give our niece an orientation; the sky was grey, the pigeons cooed on the edge of the roof, unconcerned about the plastic owls on the one next door. To the north, we could see planes on their flight path headed for Trudeau and Mirabel, and in between, the low roofs of the two- and three-story apartments in our neighborhood; trees in shades of green, russet, red; the oocasional modern high-rise; and the churches, rising from the city parishes, spaced ten blocks or so apart.

My niece and I went for a walk afterwards, up to Av. Mont-Royal where we went to the meat and produce markets; the pharmacy; a shoe store where we oogled some lace-up boxer-type boots in a choice of red or orange suede. She's a writer, too, and she was soaking up the ambience of the city and noticing everything: the dogs, the bicycles, the packages of quail and rabbit, the French skincare products in the pharmacy window; the women with their unstudied but lovely style. It was raining by then and I asked if she wanted to head back. "Oh, no. You have no idea how good this feels to a person from L.A.," she said, turning her damp head toward me and smiling. "We haven't had rain since February. I feel like all my cells are re-hydrating."

Our last stop was the bakery for a baguette, a few croissants pour le matin, a thin slice of creamy brie. "I'm convinced," she said. "It's heaven."

Vraiment, but wait until February comes around again, and I am writing about something quite different from rain!

5:21 PM

|

Friday, October 01, 2004

AGORA: LE DOMAINE PUBLIC

“A city isn’t just a place to live, to shop, to go out and have kids play.

It’s a place that implicates how one derives one’s ethics,

how one develops a sense of justice, how one learns to talk with

and learns from people who are unlike oneself, which is how

a human being becomes human.”

Richard Sennett, The Civitas of Seeing (1989)

UNE FEUILLE D'ERABLE BLEUE (A BLUE MAPLE LEAF) by West 8 Urban Design & Landscape Architecture

Today I picked up a copy of “Agora: le domaine public”. Not knowing what this was, but seeing that it had something to do with art, I sat down later to read the booklet. It is for “la Biennale de Montreal”, between the 24th of September and the 31st of October, and appears to be a regularly-occurring event during which an art theme is publicly explored and discussed. This year’s theme is Public Art. The booklet contains written material explaining this year’s events, and the works that are being produced in major public spaces in conjunction with it. One of the most interesting will be created at the Place des Arts “many stripped tree trunks will be assembled” into a tall, cubic shape that contains an empty space that can be entered. When the viewer looks up from inside, and below, the shape will form a view of the sky that is – a blue maple leaf.

The purpose of this month-long examination stems from change in what we perceive as the agora, the public meeting space that has traditionally been at the heart of cities:

“In the world at large – and even here – the pulse of public space is weakening…our public spaces are increasingly defined by a bricolage of carefully selected, often homogenous experiences…meanwhile, our growing preference for privacy has carved a bunker-like network of subterranean consumer malls – anonymous, climate-controlled sanctuaries where the cash register reigns. Are these our agoras?”

“The Biennale will gather some of the world’s foremost artists , architects, urban designers, and landscape designers to respond to these multi-faceted questions and raise new ones…and you – the public – are invited to attend and participate.”

In addition to the “real” art installations and projects I am looking forward to seeing, one of the projects is called “La ville virtuelle” (the virtual city), a concept introduced by these words:

“In this context, Web-based art is surely the public art par excellence, universally accessible and free from mediation by the traditional institutions of galleries and museums. But what are the real implications of this medium for artists, for the artistic milieu, for the public? Where do artists and their works stand within this virtual city? And how can web-based art help us to navigate the pathways of the virtual city itself – be it as a utopian place, a metaphorical device, or a critical tool?”

Stay tuned.

7:13 PM

|

|

|