Tuesday, August 31, 2004

END OF SUMMER

Lake Winnepesauke, New Hampshire

The first sound I heard in the woods nearby was a pileated woodpecker; the second was this (scroll down and play the "tremolo").

Rather than say much, I'll leave you with that call of wildness, and the silence that follows it. It was a restorative day, filled to overflowing with dear old friends, wild blueberry cake and homemade peach ice cream, children growing up, memories of my own childhood on a lake and of all these people when we were younger, coming to the same place, doing the same things. Gratitude, peacefulness: floating on my back, all alone, feeling the waves rippling over my body and the water supporting it, seeing nothing but blue sky and the tops of the white pines that stand guard over the shoreline.

Travel day tomorrow and a blogger meeting; more on Thursday. I hope others will contribute to the ongoing, great discussion of the previous post.

5:42 PM

|

Monday, August 30, 2004

There is the beginning of a very good discussion in the comment thread on the previous post, about "love" of America. The political argument and kneejerk response is obvous: as Chris said and those of us who lived through Vietnam remember only too well, criticism doesn't mean a lack of love for one's country. Many of us do have a quick emotional response if our criticism is confronted: "I do love America!" and often go into the riff about how one can love America and hate the government's policies, and so forth - for this, see the previous comments. Obviously love of one's country - that often arbitrary division of our planet into political/economic/social/linguistic entities, subject to one dominant group's definition over potential others' - has led to some terrible things. But it is also possible, I hope, to think of those divisions with intelligence, affection and humor, and to go beyond the oft-repeated repartee.

What DOES "love" mean in this context? I love the land, and the great cities, I love "My Antonia" and "Huck Finn" and "Franny and Zooey" just as I love the people I've known who are quintessentially "American" in the way those books and characters are... Is America its people, or its government, or the land that comprises it? Its artists and writers? Is it a particular spirit or ideal that can be defined - God knows the politicians are trying! Looking just at American art (all mediums) is there something we can pin down or identify that makes it "American"?

I'd love to hear from other readers on this expanding topic....

7:55 AM

|

Saturday, August 28, 2004

Bikes parked on rue Laurier, Montreal

CYCLISTS PROTEST REPUBLICANS AND ANTI-ENVIRONMENTAL POLICIES IN NYC

Yesterday, thousands of cyclists materialized, seemingly out of nowhere, and rode through New York City streets and Times Square to protest President Bush and the Republicans. Sadly, police reacted, at times violently. At latest count, 264 of the protesters were arrested. The New York Times article is here; check these links for a Bikes Not Bombs report from Scorcher, with links to photos, video and more stories. There are some good pictures at nyc.indymedia, and more, showing the real spirit of the Critical Mass bike protest, at GammaBlaBlog. You can also visit the Talk Fast Ride Slow/Critical Mass website, with an explanation of the movement that started 10 years ago in San Francisco, and opportunities to support the organization through a few nifty posters and products (like a small yellow license plate that reads: "BICYCLING: A Quiet Protest AGAINST OIL WARS").

The ride is known as a Critical Mass, a bike ride that claims no organizers and simply materializes, thanks to leaflets and Internet messages, on the last Friday of every month. The rides have been held in New York for the last several years, and are usually tolerated by the police, who in the past have cited only a few riders for traffic violations and have sometimes even escorted the group.

The rides are meant to protest cars and their pollution, but the ride last night was advertised as the R.N.C. Critical Mass, and scores of riders wore clothes or carried signs with messages against the convention and President Bush. Others wore fanciful attire, like a woman who rode in a peach wedding dress. One woman pushed her friend in a shopping cart...

Yeah! Here's to bikes and bike riders. J. and I brought our bikes back to Vermont this time, and we've been shocked at how difficult it is to find a safe, let alone pleasant, place to ride - even in this "green" state. The road along the river where I used to ride, years ago, is in lousy shape, with potholes, cave-ins and distorted pavement, loose gravel and glass, ruts and crevasses that could easily spill a road bike. Even at 9:30 am, when commuters had gone to work and traffic was light, there were many pickups and larger trucks whizzing by. Some gave me a wide berth; some did not. Luckily there was a big shoulder - but it had all the problems mentioned above. I got a good workout, and enjoyed the sections of the road that paralleled the river, but with the amount of attention I had to pay, in all directions, it certainly wasn't relaxing.

J. had gone in a different direction, through the nearby towns, and came back to say that he had felt in danger the entire time; many of the places he had been riding have no shoulder and no provision for bikes or pedestrians - and the drivers are completely unaccustomed to looking for either. Except for serious cyclists in fish-suits, and the packs of often-bedraggled bike tour groups who appear on highways and backroads throughout the Vermont summer, their presence signalled by bouncing red flags atop long flexible wires attached to the bikes, the only people who ride bikes here are those who have no other means of transportation. "It was weird, the way people were looking at me," J. said. "And then I realized it's because once they saw I wasn't a kid, they expected me to be somebody poor or eccentric, which meant somebody kind of shady who they needed to check out and maybe be wary of."

I was more concerned about not getting hurt myself. One red pick-up whizzed past me, and I saw that the driver was carrying several 2 x 6s in the back, all of them tipped diagonally in the bed and overhanging the right-hand side of the road by several feet. "Jeez," I thought, feeling the hairs prickle on the back of my neck under my helmet. Later that evening we talked to a family doctor who was visiting our neighbors; she works with the Navajo in New Mexico. "Yep," she said, shaking her head. "I had a woman die from something like that. She was walking along the side of the road - there are no shoulders out there where she was - and a huge RV came by and hit her in the back of the head with its mirror. She lived for a while, but she didn't make it."

The bottom line is that this is a car culture, set up for convenience and rapid mobility by automobile. Even in very small villages like mine, you are crippled without a car. Services are centralized and often no longer located in the towns and villages, but in outlying malls only reachable by car. Going anywhere under your own power is driven by youth, poverty, a desire for exercise, or it's a protest: deliberate stubbornness in the face of the prevailing culture. Even in the shopping centers, there is really no safe way to move from one destination to another without getting back in your car and driving to the next parking lot, drive-up bank, or fast food outlet. People even move their cars within the huge parking lots that span the distance between the giant box-stores, to avoid walking - and judging from the labored gait and breathing of many of these customers, they need to. What have we exchanged for convenience?

I saw all this before, but never so clearly. The minute we cross the border back into the U.S., the vehicles balloon in size, the aggressiveness of the driving increases --- and the price of gasoline - though expensive, to be sure - goes down.

10:14 AM

|

Friday, August 27, 2004

Some links:

Sharia Law in Canada? The Canadian government is considering a proposal by Muslims to be allowed to arbitrate disputes using Islamic law. It brings up the question of whether Jews and Muslims are receiving equal freedom in the use of religious laws, but even more importantly, it is forcing both the Canadian government and Muslims themselves to talk about who they are and what they want society to be. The most vociferous opposition is coming from Iranian women who came to Canada to escape Sharia law; on the other side of the questions are some feminist Islamic women who see this as a chance to contribute to the reform of Islamic law. From the BBC.

"Marion Boyd, a lawyer and former feminist activist, has been asked by the Ontario Government to review the arbitration act which allows religious groups to settle civil disputes using their own courts...She hinted strongly to me that the government could not allow Jewish courts and forbid Muslim ones; that would be discrimination. But Ms Boyd stressed that decisions reached by Muslim courts would have to be consistent with Canada's charter of rights and freedoms. "

BY APPOINTMENT TO THE QUEEN...THE AMERICAN WOMAN

Feminists of a modern persuasion might want to take a look at "La Femme", a car once offered by Dodge to the American female market. I think even those who cannot read French may be able to figure out from the text what accoutrements Dodge offered for its female customers. Amazing. From the eclectic, intelligent, droll, and often poetic blog of a new Montreal friend, Zenon, a "laupe" for sure.

EYEWITNESS IN NAJAF

An eyewitness account of Najaf under seige, written earlier this week, from Al-Ahram Weekly.

WOMEN SINGERS IN IRAN

This account, via Payyvand, tells of a concert in Iran by a famous female singer, attended by 1000 women, from which all men were barred:

The audience is a mixture of women dressed head to toe in the traditional all-black chador and others who take advantage of the absence of men by removing their veils and even watch the show in sleeveless tops... Herself a musician and composer, Hashemi admits women performers are still having a hard time changing the view of the Islamic regime that a woman's voice is provocative and arouses devious sexual thoughts in men... "Men do not trust themselves. They are afraid that women will grow stronger and flourish," is her view on the restrictions she faces..."Unlike men we have absolutely no chance of being professionals in this industry, so it has to be our second job," she complained. "My biggest wish is to make a pop record. Traditional music is alright but it does not respond to our current needs -- joyfulness and fun."

9:16 AM

|

Thursday, August 26, 2004

ON ANGELS

Czeslaw Milosz

All was taken away from you: white dresses,

wings, even existence.

Yet I believe you,

messengers.

There, where the world is turned inside out,

a heavy fabric embroidered with stars and beasts,

you stroll, inspecting the trustworthy seams.

Short is your stay here:

now and then at a matinal hour, if the sky is clear,

in a melody repeated by a bird,

or in the smell of apples at the close of day

when the light makes the orchards magic.

They say somebody has invented you

but to me this does not sound convincing

for humans invented themselves as well.

The voice - no doubt it is a valid proof,

as it can belong only to radiant creatures,

weightless and winged (after all, why not?),

girdled with the lightening.

I have heard that voice many a time when asleep

and, what is strange, I understood more or less

an order or an appeal in an unearthly tongue:

day draws near

another one

do what you can.

(1969)

2:46 PM

|

Wednesday, August 25, 2004

WISH YOU WERE HERE

This is my 500th post.

We're back in Vermont, J. is mowing the lawn, and I'm celebrating, or maybe I should say contemplating, this event all alone with my tea and a blackcurrant chocolate bar from the Polish company E. Wedel. It's delicious but, I confess, I bought it for the packaging. On the marvelously yellow wrapper it says, in blue letters, "czekolada mleczna" - milk chocolate? and "porzeczkowa", which must be blackcurrent. How do you say that prickly mouthful of wonderful word? I didn't think of it, but maybe I bought it for Milosz and all those other Polish poets who have appeared here beside me from time to time during these strange and fruitful seventeen months of blogging.

As we drove east out of the city early this morning, toward a blinding, rising fireball exactly lined up with the bridge - not unlike that wild and freely rolling orb in Burnt by the Sun - I began thinking about 500 posts. Good Lord. I don't even want to do the math, but let's see: at 500 words each (a very conservative estimate, since many have - and this is a testament to the patience of you readers - run to 1500 words or more of small hard-to-read type), let me repeat, at 500 words each that would be 250,000 words. A minimum of 250,000 fairly carefully considered words, from the pen of someone who is trying to, ahem, write a book. And the total is probably closer to 500,000.

Sigh.

And yet, not-sigh.

A long time ago, making excuses for not doing something I had told myself I "ought" to be doing, I owned up to the fact that we find time to do the things we really want to do. At different points in my life, those things have taken different forms. I used to find time to make my own clothes. Paint. Tend a vegetable garden. Practice the piano and take lessons. We spent several winters, rather long ago, watching practically every Celtics game: an expenditure of time that seems inconceivable to me now. I don't do those things now, not that I wouldn't still like to; it's just that my priorities are different, and certain other things float to the top of the ever-full laundry basket, so to speak. Now I find time to blog, and to think about blogging, and to communicate with other bloggers, and I procrastinate sometimes even when it comes to other writing, writing I know I really do want to do.

So, to sound like Augustine for a minute: What Does It Mean?

It's simple: I get more out of this than most other things, so I keep doing it. It fits. It feels like me.

Flashback to a memory, on the sidewalk outside my elementary school. I'm talking to a teacher, and she is asking me what I want to do when I grow up. And I say, "I think I'd like to write books and illustrate them." How old was I? 10? And why do I remember that moment, instead of all the other times I was asked that question, times when it actually counted, when by my answer, verbalized or not, I made decisions that took me further and further away from that spontaneous, honest, and true-to-myself one-sentence statement made as a child?

Learning who we really are often means unlearning what others want us to be. It helps to go back and replay scenes from our childhood. It helps to see what and who inspire us, and what we return to again and again. It helps to think about what brings us to tears.

For me, it's most often words. Once in a while my own, but most often someone else's. I've tried, and even gotten pretty good at, other forms of expression, but I think words are the most natural way for me to do that unenviable and ever-unfinished task of the artist: trying to express the unexpressible.

But I am neither novelist nor researcher, and I am not a true poet. I'm a letter-writer. I've always written letters, and taken that form seriously. I was a diarist for a very long time before I was an essayist, and my essays have always read like letters. Even writing in a diary has never been something I did for myself, entirely alone. In a corner of the room there have been the spirits of other writers whose words inspire me, and sitting near my desk has always been the hoped-for reader, holding the words in their hands... anonymously, even posthumously...and in my imagination, they always understand. For me, writing is about conversation; my desire to express is not about the sound of my own words, but a desire to listen, to answer, and to exchange, in the hope of communion.

So I'm not apologizing for lavishly pouring out all those words, like the Biblical woman's precious oil, into a new medium, and neglecting, sometimes, the more traditional path. Nothing I've ever done has come close to making those pictures in my imagination - the girl on the sidewalk; the curious, empathetic, critical reader by my elbow - more alive than blogging has.

You, known and unknown, are an essential part of that picture, and so -- I thank you. Chocolate for everybody!

4:41 PM

|

Monday, August 23, 2004

FLEURS by the FLEUVE - women waiting to have their portrait taken at a park on the St. Lawrence. That's the Biosphere, from the Montreal World's Fair, in the distance.

On Sunday, a beautiful late summer day with a stiff but warm wind, we took our longest bike ride to date, and probably my longest ride ever: from our apartment through Parc LaFontaine and south across the Pont Jacques Cartier to Parc Jean Drapeau, site of the Montreal World's Fair; then across the Pont de la Concorde to Point du Havre, the entrance to the old port; then down along the port, past Habitat, along the river to the area near the old grain elevators; then back though the Old City and up St. Hubert to Sherbrooke, and through the park back home. Whew! And, incredibly, nearly all of that distance was on city bike paths. What a resource for a city - and believe me, many people were out taking advantage of it: from the sleek-suited packs of racer-jockies on their skinny thoroughbred road bikes, to a pair of Chinese women on matching royal blue reclining bikes, to parents towing their kids in buggies, on cleverly-attached training bikes, to babies happily asleep in bike seats. This is all new for me, and it is quite a discovery. Urban outdoor recreation is a fairly bizarre concept to someone who grew up in a town of 1200 and then on a small lake where all motors were forbidden, and who then lived for thirty years in an even smaller town in one rural, forested, mountainous northern New England. My idea of outdoor recreation is wilderness, and it means seeking aloneness with nature - a solitary hike, or one taken with a friend who isn't going to talk much, in a place where you aren't going to see or hear human beings. In fact, when the interstates highways got noisy enough that you could hear them from everywhere, even the woods in our region - that was when we realized that rural had crossed over into suburb. And at first, as we took a break halfway through our ride and I watched the people riding and walking and skating so happily on paved paths in a concrete city dotted with small areas of green, I wondered, "Can I adjust to this?"

So taking this bike ride was an eye-opening experience, not only because of the places where we went, but because of what I saw other people doing. In Parc Jean Drapeau were groups of people of every ethnicity, having parties, barbeques, frisbee and soccer games; near the big Calder sculpture was a teen disco party with booming techno-rock and a huge crowd of happy kids; at the other, partially overgrown venues were various configurations: a woman sketching on the shore of a pond while a woodhuck grazed about five feet from her back; old couples sitting on benches and young couples necking on blankets. The Parc itself, with the lacy Biosphere appearing behind every view like an ethereal, lacy sun, struck me as a strange and wonderful partnership of conscious human adaptation, and nature-in-progress: it is half park, and half urban ruin, with nature in the ascendency. And what a fitting metamorphosis - from the site of a World's Fair into a place where people of all races are so peacefully and happily co-existing!

We biked back across the river to Point Le Havre, another park, long and narrow, at the point where the swift St. Lawrence descends, still raging, from the Lachine Rapids and meets the much calmer water of the old port. Here, among the trees in a quieter setting, were many other family groups: a gathering of Indians with all the women in brightly colored saris; French Canadian boys throwing a football; Iranians having a traditional picnic, the men on one side of a hill grilling meat while the women, scarved and quieter, sat in a circle talking to each other out of sight of the men on the other side. We sat on the point, ate our sandwiches, and watched the boats - the quiet progress of those in the harbor, the struggle even big boats were having out in the fast current, and the various tour boats and thrill-rides on high-powered motorboat launches and hydrofoils.

Then it was off along the side of the port, down under the old grain elevators and brewery towers, where we stopped to watch ducks on the old canal, and then rode back through Vieux Montreal, the old city, thronged with tourists, horse-drawn carriage rides, bewildered pedestrians. My legs were protesting by the time we got home, but it was worth it: I had seen and learned a lot.

Late in the evening we went for a walk in the park, and ended up watching the last innings, unde the lights, of an exciting baseball game by two local teams, as entertaining for the highly-involved crowd as for the serious and accomplished play of the athletes. As we headed back north, I saw a chunky bird flutter into the grass. "A grouse?" I thought at first, confused by the shape and behavior, but then said, "Oh, look!" and grabbed J.'s arm. "It's an owl!" he whispered, and so it was - a small one, probably a screech owl. It flew up into a low branch of a crabapple, and stayed there, watching us, unmindful of our advances and my soft words of greeting, blinking and turning its head around as if to watch the co-ed softball game that had just gotten underway, and show it was bored with us.

"You say there's no wilderness in the city," said J., "but look! He's come to show you differently." I felt a rush of affection for the little owl, who looked down at me with what seemed like friendliness, or at least unconcern, and we vowed to come back and look for it often - our reminder of the wilderness that is everywhere, our little neighbor le hibou.

4:45 PM

|

Saturday, August 21, 2004

LE COUPABLE (CULPRIT)

It's an uncharacteristically grey day here, and a little cooler, making me feel that autumn is around the corner even if I can't see it. Last night we shared a dinner of pasta with sauteed red peppers, carrots, onions, mushooms, and leftover salmon, with a salad of beautiful sliced Quebec tomatoes and wrinkled oil-cured olives. Afterwards, J. did what I asked him to, and tried to open a bottle of Lebanese olive oil he had bought recently. It had a narrow neck with a gold metal cap that I hadn't been able to remove; as we've discovered before, foreign packaging can be pretty funky. Similarly unsuccessful, J. brought out a pair of vice-grips and tried to torque the cap off. I heard an expletive, and saw him head for the sink and turn on the cold water: the metal collar had stayed welded to the glass, and instead the whole neck of the bottle had broken off, slicing his hand in the fleshy part between the thumb and first finger. I got into the kitchen in two or three short steps and said, "Ok, how bad is it? Show me." He held out his hand and my stomach dove; there was a deep gash with welling, dark blood. "That needs stitches," I said.

"Where am I going to get stitched at this hour?" he replied.

"There's a clinic right over on Papineau."

"Is it open now?"

"I don't know, but it's close by."

We looked more closely at the cut. It was a pretty good one, but already bleeding less. "I think it will be all right," he said, pretty jauntily, I thought, considering the circumstances, and how upset I am whenever anything happens to my own hands. And I had to agree, it didn't look as bad as I'd first thought. "It didn't hit anything important," he said. Yeah, I thought, just your precious hand. By then we were sitting on the sofa.

"I hate it when anything happens to you," I said, holding his shoulder while he kept pressure on the cut with his other hand. "And we don't even have any gauze or pads or adhesive tape..."

"It's OK. Let's just go up to Mont Royal and get some bandages. We can ride our bikes."

"You've got to be kidding!" I said. "You can't ride your bike like that. If you can walk without it bleeding all over everything, let's walk."

So we went into the calm, still-warm night, past the nasturtiums and impatiens still glowing orange and red in the darkness, the lush ferns and shrubs in people's small street gardens. A cat, out on its own errand, led us up the block. A young woman passed us, walking in the opposite direction, wearing a denim jacket and a wool scarf wrapped around her neck.

"Have you noticed that people were here wear parkas and wool scarves in the summer?" I asked. He nodded. "Yep, I have. I guess it goes with the thing of carrying around hockey sticks all year."

The pharmacy was open, and after a brief search we stood facing a whole section of bandages, many in shapes in sizes and of types we'd never seen before. "This is interesting," I said, picking up a box of oval clear bandages.

"It certainly is," he said, equally fascinated.

"What a good sport he is," I thought, admiring him for the ten-millionth time in our long life together. We ended up with a box of German bandages and a new word -- band-aids are pansements, in French -- and a bottle of liquid bandage, something new that a friend in Boston recommended a while back, and walked back home, contentedly eating bits of a chocolate bar I happened to have in my pack.

Today his hand is sore but already healing; how amazing the body is. Knock on wood - we seem to have ducked our potential first-encounter with the Canadian health care system.

10:35 AM

|

Thursday, August 19, 2004

(To the readers who may have read this in its incomplete state last night or early this morning, apologies; the first three paragraphs got "published" without me being aware of it; to my eyes, the entire entry appeared lost when I went to bed - but voila! - here it is. Now I'll finish writing it!)

A LA BIBLIOTHEQUE

After a productive morning and half-afternoon of work, we decided to ride up to Avenue Mont-Royal and see about getting a library card at the local bibliotheque. After a leisurely bike ride, stopping once at the velo shop to buy a petite feu clignotant ( a little blinking light) to clip to our backpacks during nighttime bike rides, we arrived at the Maison de la Culture for our arrondisement and locked our bikes.

"You've got to do this one," said J., who had negotiated the blinker-purchase with aplomb. "This is way beyond my skill level."

We spoke first to a very nice young woman at an information desk for cultural events in the Plateau. Beyond her, in an exhibition hall, were brightly-colored drawings. "We have just moved here and we have a few questions," I said. She smiled, and to our surprise, stood up to talk to us. I can't remember the last time anybody behind a desk did that.

"Oui," she said, "and bienvenue! I will do my best to help you." We asked if, as property owners and parttime residents of the Plateau, we would have access to various facilities like the libraries and swimming pools, or the many classes offered by the cultural wing of the local government (and subsidized by the city - through taxes). "I believe you can have access to all of these," she told us, pursing her lips in that so-French way, "and why not, you are here, you are paying taxes, correct?"

She explained that we did have to show proof of residency at the library, and smiled warmly again. "You can go and see, just here," she said, gesturing toward the door to our right that led back into the Mont-Royal branch of the library. "Your cards will work at any branch though."

So we went back into the library and went up to the desk, waiting for four people to check out their books. The person we spoke to was a thin, wiry man; precise and rather solemn; and so soft-spoken that we had to lean close to hear him. I spoke my usual mixture of French and English, and the more French I spoke, the more it seemed he warmed up. "Do you have proof of residency?" he inquired. "The permitted forms are a local driver's license, utility bills in your names showing your Montreal address, a bank account statement in your name with the address..."

J. had come prepared, and he handed the librarian a Hydro-Quebec bill, the contract for our apartment, and a bank statement. "No," said the librarian, looking at the contract. "This is not a permitted form." He handed it back to us, and turned to the statement from the Royal Bank. "And this statement has a P.O. Box for your address, and it is in Vermont." We looked and it was true.

"Well, then can you use the Hydo-Quebec bill?" J. asked.

The librarain studied it. "Yes," he said, "here it all is, the street address...but," he looked up at me, "your name is not listed, only your husband's."

"Well, yes," I said, "the utility bills are not in my name, but the bank account is joint."

"Yes, but it doesn't show your address in Montreal."

J., who was already being much more patient with these regulations than he usually is, said, "But the contract has a clause in it showing that we are married. Can't you.."

"No," said the librarian, looking a little more sympathetic, and even slightly amused at us, "I am sorry. It is not permitted...Shall we do yours, though?" While J. and I discussed how to get a proof that would work for me, the librarian started filling out the forms and wrote J.'s name on a white plastic card with a marker, then cut a piece of clear plastic tape and stuck it over the letters to keep them from smearing. Doing this activity seemed to soften his manner. "Here," he said, "do you read any French?" I said I did. "I'll give you the library information in English, though, it will be easier for you." He handed J. the card. "This is your card, it will work in any one of the libraries, and you can also return books from here to any branch. You can take out a maximum of 25 documents at one time." He explained the rules for fines on overdue books, and we nodded. Then he suddenly leaned forward and whispered to J., almost conspiratorially, "Your wife can use your card anytime, you know. Anyone can use it! But you are responsible. Okay?"

We smiled, suddenly relieved - our local university library cards cost $100 a year and are not transferable, ever - and took the books and papers from him, stashed everything back in J.'s knapsack, and began looking around. The library was in three sections: the children's area, fiction and periodicals - here, this being the Plateau, there were perhaps six very long stacks of romans francais (French novels), one of English, a section of Spanish books, and a large collection of graphic novels, and another section devoted to non-fiction. "My God," said J. "it's Dewey-Decimal." And it was, the first Dewey-Decimal system I've seen in probably thirty years (although I'm sure it's still used in many parts of the U.S.) "Well," I laughed, "it's not as if the Library of Congress applies here. I used to know this system by heart." "So did I," he said, looking about us with wonder.

Everything in the rooms felt old-fashioned; except for the computers, which had a very quick and easy look-up system for the central catalog, the library felt like a time-warp. People sat at long tables reading, taking copious notes by hand on lined paper. An old man peered at a newspaper through a magnifying glass. There were a few comfortable upholstered chairs, but not many; the basic feeling was like a standard high school library from the early seventies - but that is not a criticism! I liked it. There was a respectful air in the room, as if the people were serious, and a code of silence was agreed upon. "Look," I whispered, gesturing toward one of the little desks against one wall, with a label saying something in french that i took to mean "language practice station". Set into the desk was one of those little machines from high school French language lab, with buttons for "forward" and "repetez". "It was always a good way to learn," I said.

J. chose a book - an atlas of historic Montreal - and took it up to the desk. A different librarian took it from him and then shook her head. "You see," she said, showing him the spine, "this is from the reference section and it doesn't circulate. But ask one of the librarians. I am sure we have something similar that you can take out." She handed it back to him, and, shaking our heads in wonder at our own denseness, we trudged back and replaced the book.

"OK," said J. "That's enough for today," and we went out to practice, one again, the new routine of managing bike locks and knapsacks and keys and helmets without feeling or appearing completely clumsy. We looked at each other and laughed. J. said, "It's simple. First you learn how to get a card. Then you learn how to take out a book... want to go explore some more before we go home?" and off we rode, down a new street.

9:28 PM

|

Wednesday, August 18, 2004

On the drive up here to Montreal, we pass a highway sign that reads "45 degrees north. Halfway between the equator and the North Pole." That's pretty far north, some of you might think, as I used to. But after I stood, a year or two ago, staring at a huge map of Canada on one wall of the McCord Museum in Montreal, I realized that those additional 45 degrees contained an enormous landmass about which I knew very little. To me it was just - the north. Polar bears. Tundra. Snowy owls. Hudson's Bay, Labrador, and lost explorers; ice-breakers and the cries of ptarmigan.

When you look at a map of Quebec, where I live, there is a busy-ness of names and dots marking the cities and towns, the populated areas of the province, along the southern edges of the map, next to the familar cities and towns of the northeastern United States. But unfold the map, and keep unfolding...to the north of Montreal and Quebec City lies a vastness with nary a dot at all, just a land of lakes and mountains and then flat tundra stretching north, north, always north. The distances are big too, mirroring the dislocation from all that is familiar. Today a friend sent an email about a recent trip to the Sageunay River, a six-hour trip up the St. Lawrence from here by car.

"The three-hour sea kayaking excursion was all we could have hoped for and more. We paddled upriver, close to the large granite boulders which made up the shore of this deep (350 m) river. We snuck up on a seal playing along the edge. We crossed over to the other side just as the tide was changing, offering us one wave to test our sea-worthiness. After a break grazing on low bush blueberries and a neat apple-like berry, we headed home. As we were once again crossing the river, we spied the white backs of breaching beluga whales. This was thrilling in itself. I hadn’t realized they swam upriver to play.

Well, while we sat in our kayaks in the middle of the river, we were slowly approached by these amazing mammals. They came up and explored us. One breached right behind my husband (in the back of our two person kayak) and then swam up to me, turning slightly to look up and say hi with his fin (at least that is what it felt like). We couldn’t have asked for a more intimate encounter."

Here in this city, where right now I hear the cries of seagulls from the St. Lawrence, into whose gulf those whales had swum, such stories of the northern wilderness feel far away. The brevity of summer, however, cannot be ignored. I can already detect a difference in the length of the days, and the changes are more noticeable because of our week-long absences. Last night I watched the sunlight fade at dinnertime, considerably earlier than when we first started living in the city a month ago. We went for a walk in the park to catch the fading light, stopping to watch a couple of innings of little league baseball, and then following the curve of the lake while children flung their last breadcrumbs to the flock of waiting ducks. People of all ages sat on the green benches along the water, watching the play of the fountain, talking, reading, while others glided by on bicycles or rollerblades. Under the trees, three men sat playing guitars and singing; lovers lay together on blankets; family groups finished up their picnics. "There's a catalpa," I said, pointing the tree out to J. "I'm just beginning to notice individuals - trees, people - everything up to now has been overall impressions." He nodded, agreeing. Feeling the fingers of fall, I felt slightly melancholy, but as we walked up the allee of trees back toward the street, with J.'s arm warming my shoulders, we passed a young woman on a bench, writing intently in a notebook, and I said, "This is going to be a wonderful place to be a writer."

10:06 AM

|

Monday, August 16, 2004

A couple nights ago, tired, we ate at the local diner. It’s a five-minute car ride from the house, and is the real thing: a semi-restored original with a metal exterior and linoleum floor, a long counter with swivel-stools, and jukeboxes in each booth. A white board near the entrance listed the Friday night specials: roast beef dinner for $10.95, baked or fried haddock for 9.95, or a fisherman’s platter for $12. We sat down and said hi to the waitress, who brought menus and paper placemats with ads for local businesses printed in red ink. She came back in a few minutes and asked, “What’ll you have?” J. ordered a hamburger with fries: $4.95. I asked for a fried fish sandwich with a side order of baked beans -- OK, a little weird but I felt like eating baked beans, and J. dislikes them so I only get them at potlucks or a diner. “Do you want fries with that?” she asked. “Onion rings?” I looked dubious. “How about sweet potato fries?” “OK,” I said, giving in.

Our dinners arrived. Mine wasn’t a standard fish burger at all, but a real piece of fried haddock, not greasy, in a bun with a slice of tomato and some curly lettuce. The baked beans came in their own little beanpot, swimming in a sweet, thick molasses sauce with pieces of salt pork, and the sweet potato fries were delicious. We ate quietly, listening to the conversations around us and reading the signs on the wall behind the cash register:

“Everyone here brings happiness…some by leaving, some by coming in.”

“This is not Burger King. You don’t get it your way, you take it my way, or you don’t get the damn thing.”

“The complaint department is in the back…he’s the big bald guy wearing leather and riding the Harley…good luck!”

“Do you think the jukebox works?” I asked J. “Don’t know,” he said. I fished out a quarter and chose two old Patsy Kline songs from the faded list of pink, blue and pale green titles, punching in #140 and #240. Nothing. “Guess not,” I said, and when the waitress came to settle up the bill we mentioned that the jukebox didn’t work. “How much did you put in?” she asked. “A quarter,” we said, and she immediately handed us one from her apron pocket. “I’m trying to get somebody to come and repair them,” she said. “Do any of them work?” I asked. “Nope,” she said, shaking her head. “More coffee?”

An older guy came in and sat down at the counter. He was heavy and tired, and told the younger waitress it had been a long day at work. He was wearing a black t-shirt and shorts with a big chain looped up to his waist, and black leather ankle-high lace-up boots, and just above the right one he had an angry-looking burn on his leg. He propped himself on the counter and sighed heavily. “What shall I eat tonight?” he was asking as we got up to leave. “The meatloaf's pretty good, I think you’d like it,” the waitress told him, sweetly, and he said, “OK, I’ll have it,” as we walked out the door.

1:19 PM

|

Saturday, August 14, 2004

SAD NEWS

Czeslaw Milosz has died at his home in Krakow, at the age of 93.

Milosz is one of the poets who most speaks to me, and in the last year or two, diving into his huge oeuvre, I've come up again and again, breathless at his clarity, his humility, his directness in speaking about the human condition. And because of his very long life and relatively good health that allowed him to continue to write, he had many years to consider his mortality, as well as his oft-explored themes of sensual pleasure and personal happiness amid a continual awareness of the world's suffering, and his struggles to understand God and his own battered faith.

Just now I looked briefly through his New and Collected Poems for something appropriate on this day - which almost any poem of his would be. There was too much choice. Here is one - a longish poem he wrote on the occasion of turning seventy, twenty-three years ago.

POET AT SEVENTY

Thus, brother theologian, here you are.

Connoisseur of heavens and abysses,

Year after year perfecting your art,

Choosing bookish wisdom for your mistress,

Only to discover you wander in the dark.

Ai, humiliated to the bone

By tricks that crafty reason plays,

You searched for peace in human homes

But they, like sailboats, glide away,

Their goal and port, alas, unknown.

You sit in taverns drinking wine,

Pleased by the hubbub and the din,

Voices grow loud and then decline

As if played out by a machine

And you accept your quarantine.

On this sad earth no time to grieve,

Love potions every spring are brewing,

Your heart, in magic, finds relief,

Though Lenten dirges cut your cooing.

And thus you learn how to forgive.

Voracious, frivolous, and dazed

As if your time were without end

You run around and loudly praise

Theatrum where the flesh pretends

To win the game of nights and days.

In plumes and scales to fly and crawl,

Put on mascara, fluffy dresses,

Attempt to play like beast and fowl,

Forgetting interstellar spaces:

Try, my philosopher, the world.

And all your wisdom came to nothing

Though many years you worked and strived

With only one reward and trophy:

your happiness to be alive

And sorrow that your life is closing.

Not willing to stop reading his words, I continued leafing through the book, and near the end I found this, which brought me to tears:

PRAYER

Approaching ninety, and still with a hope

That I could tell it, say it, blurt it out.

If not before people, at least before You,

Who nourished me with honey and wormwood.

I am ashamed, for I must believe you protected me,

As if I had for You some pearticular merit.

I was like those in the gulags who fashioned a cross from twigs

And prayed to it at night in the barraks.

I made a plea and You deigned to answer it,

So that I could see how unreasonable it was.

But when out of pity for others I begged a miracle,

The sky and the earth were silent, as always.

Morally suspect becasue of my belief in You,

I admired unbelievers for their simple persistence.

What sort of adorer of Majesty am I,

If I consider religion good only for the weak like myself?

The least-normal person in Father Chomski's class,

I had already fixed my sights on the swirling vortex of a destiny.

Now You are closing down my five sense, slowly,

And I am an old man lying in darkness.

Delivered to that thing which has oppressed me

So that I always ran forward, composing poems.

Liberate me from guilt, real and imagined.

Give me certainty that I toiled for Your glory.

In the hour of the agony of death, help me with Your suffering

Which cannot save the world from pain.

10:19 AM

|

Friday, August 13, 2004

MORE ART TALK

I agree with elck, in his comments on the last post, that America's big cities abound in cultural opportunities, and that of those, the visual arts are often the most accessible and affordable. I also agree that in the academy, arts education is excellent - but especially once you're out of the city, academic taste often becomes rarified and distant from local cultures, with the university acting as arbiter of what is "good" art in all sorts of ways, from hosting and jurying art shows to lending its "poets" for local readings, always on a "higher" level than people who come up from, and express, the grass roots. I have a big problem with that.

We started out with Marja-Leena's comment that in Canada, she felt the visual arts were less well funded than other forms, and visual arts education less than adequate. My contention is that in America, there is a certain appreciation for the visual arts - I think we are a pretty visually-oriented culture - and most kids do receive some visual arts education. But I'd never say that the culture at large supports, or understands, or has a language for, or is comfortable with, painting, photography, and sculpture, especially the contemporary versions of these. I've spent my life in the visual arts and in communicating (or trying to) about visual art and design with other people. On the non-professional side, I did one stint as board member of a local arts organization during the years when we were starting an arts education program for adults and children. I was on that education committee for seven years. The program has been a rousing success, but this is in a region with a lot of sophisticated, educated people who aren't afraid of art. There has also been a tireless director who has worked with local schools to identify gifted children and give them the opportunity for further study, funded by scholarships that she has funded through grants and local business connections. There are also programs for seniors. This kind of thing takes a huge amount of dedication and work, but it is wonderful when it happens and endures.

On the other hand, my rural public school, in unsophisticated farm country, had one of the best music programs in the state of New York, largely due to the efforts of two totally dedicated teachers - the band and choir directors - who taught every kid in that school system to read music and love it. That was thirty and forty years ago. To this day, there are poor families in that area who make sure their kids play in the band or who, as adults, still play in the little local community bands themselves or take part in local theater productions. There was also a thriving visual arts society because one woman made it her life's work - and these three people all had a huge effect on my life. That school system was an example of local people deciding that music was just as important as football. When you have a hundred kids who've learned about the lives of composers, and played music from Bach to Bernstein, and gone back and talked to their families about it after dairy barn chores, it tends to bring the adults along and change the pooh-poohing, which is a product of the fear of being found ignorant, to acceptance. All those families used to show up for concerts and parades; maybe they still liked the Sousa marches better than Gustav Holst, but they came. Looking back, I see how remarkable this was and how it had a lasting effect on a lot of people.

What it takes is often not so much money, but heart and dedication, and gifted communicators. We say that only the rich or well-educated appreciate art in our society, but I think we can do a lot to change that by getting out in the community and making art real, and showing that artists are real - that living an artist's life is worthwhile and important even though it is difficult. Modern society has a real tendency to shift the responsibility for everything onto government, and then blame it for all the failures. While I deplore the cutbacks in arts funding, and, even more, deplore the fact that we are spending money on bombs rather than programs that benefit people, local people and communities can insist that the arts are important - and one articulate or energetic person can actually make a big difference. I agree, though, that the tendency in our culture is in an opposite direction and that fighting this fight is increasingly difficult. Yet we are talking about a basic need and hunger that people have, even more so in an environment that is suffused with fear, anxiety, and hopelessness.

2:26 PM

|

Thursday, August 12, 2004

ART APPRECIATION

In the comments on last night's post, Marja-Leena wrote this about Canada:

I think that many people have difficulty understanding visual arts, particularly contemporary art, and I blame our deficient-in-art education system partly for that. Generally speaking Europeans seem better educated and more interested in it, and they have all those wonderful museums too. Music-based performing arts has always been part of life and does not seem so challenging to enjoy, don't you think? How do you find this compares to the US? The big cities have many wonderful museums having a greater population and wealth to support them. Are they well attended?

I wonder if others would like to comment. How does appreciation of the various arts vary across the US?

7:33 AM

|

Wednesday, August 11, 2004

Ernesto's recent posts at Never Neutral have moved me, especially his musings about the difficulties of being a writer in a society that doesn't feel supportive of literature or writing, that doesn't, in his words, read. Although I've written about the shock and delight of seeing Montrealers reading on the metro, on buses, in the parks, and even walking, I really don't know enough about the society yet to know if it loves literature and writers. According to Marja-Leena, Canada does support its artists, and a large percentage of the annual arts budget goes to writers. How that translates into everyday reality I have yet to discover, and as a non-Canadian I won't be able to benefit from it except indirectly - but indirect is good too.

Coming back and forth, as we are now doing, forces one to see differences and similarities, and it's also forcing some stark reassessments of priorities. The early indications I had, back in May, that this big old house might prove to be more of a burden than blessing have certainly proved to be true. My growing awareness that what I want to do most is take care of myself, my marriage, my primary relationships, and write, has forced me to notice all the other things that I've gotten enmeshed in, or that I've used to fill up perceived gaps, distract myself, or avoid boredom and even commitment. I don't feel guilty about that, or ashamed, but I'm glad to be figuring it out. I'm also glad to be able to see that our societal bias toward more being the path to happiness and liberation is, for me, just the opposite: a trap that ensnares and limits me and my already limited energy. I want less: less space, fewer possessions, fewer obligations, a lighter step, more freedom of movement and spirit. I'm figuring out that what I really need from the material world is a bed, a place to cook and to wash, and a mental space that is as free as possible for contemplation and creative thinking - although, having been there at earlier points in my life, I know how difficult it can be to be creative when one is worrying constantly about money.

Writing is...what I need to do. It's almost involuntary. It almost doesn't matter if anyone reads it: I kept a private journal for years and years before ever beginning to blog. We have this affliction, writers do, and like Jacob, wounded in the thigh from wrestling with the angel, forever afterwards we limp, but we can't go back to the way we were before we saw ourselves as writers.

6:00 PM

|

Tuesday, August 10, 2004

SUNDAY WAS MARKET DAY

On Sunday we rode our bikes to the Jean-Talon market - a revelation. We've been to this vast semi-open-air farmer's market many times, but always by car. It seemed as if it would take forever to get there by bike, but no - maybe twenty minutes, and we were there. We spent about two hours browsing on the visual feast, and then rode home.

Now we're back in Vermont. I spent the morning interviewing Doug Theuner, the former bishop of New Hampshire, and have two more interviews scheduled for Thursday, so that project is proceeding. I'm finding the transition between the two homes and lives quite difficult, though, and am hoping it will get easier.

And I am so far behind on writing here! There are more stories from the trip last week across New York State, and a moral fable from Montreal, and impressions of three films: Fahrenheit 911, Maria Full of Grace, and Spring Summer Fall Winter and Spring. So stay tuned.

6:10 PM

|

Thursday, August 05, 2004

MONTREAL and the St. Lawrence river, from the Pont Jacques Cartier.

We've been doing a lot of biking in this ultimately velo-friendly city, and a few days ago rode up onto the Jacques Cartier bridge, which spans the St. Lawrence on the eastern side of the city. The island you see on the left is only partway across the river; the St. Lawrence is huge. I stood on the bridge for what felt like hours as the sun went down over the city, watching the light play on the steel and glass surfaces of the downtown skyscrapers, witnessing the ponderous advance of a giant container ship into the port, and the mosquito-like darting of tiny white cigarette boats below me. All the while the air was filled with the smells of the river and the pungency of hops, appropriately perfuming the city from the Molson plant that dominates the shoreline. It was an extraordinary evening, and there was a steady stream of cyclists and walkers of every age and ethnicity, most of whom - not matter how hip or hurried - paused for a few minutes to look out over their city.

--

When meeting bloggers in the flesh, one must expect the unexpected. Wednesday night I attended my first meeting of a Montreal bloggers' group. It takes place on the first Wednesday of every month at a friendly, noisy bar/resto within walking distance of our apartment. The instructions said to come any time between 8:00 and midnight, so we walked over and arrived about 9:30. No sign of the stuffed cow that Patrick had promised, and I had imagined hanging on a wall abover the designated table, so finally we shyly asked the largest group if they were bloggers. "Oui! Yes!" came the bilingual reply, with sounds of chairs being pulled out for us. Several of the bloggers there already knew and read "Cassandra", so there was a warm welcome, but I think it would have been warm anyway; this was a congenial crowd of a dozen or so. "Ou est la vache?" I inquired. "Voila!" said Patrick, holding up a small stuffed cow doll with a rakish grin, perched on the table between the espresso cups and beer glasses.

J. immediately fell into conversation with Martine and Blork. Painter/writer/programmer Maciej was at the second table. Across from me sat a philosopher-blogger who writes under the nom de plume of Zenon. "Pourquoi 'Cassandra'"? he asked, and off we went into a two-hour conversation about metaphysics and religion; he had come to the Plateau earlier that afternoon to browse some of the many good used-book stores and had found a treasure, L'oeil du coeur of Frithjof Schuon , to whose work and thought I was introduced during the evening. At about 11:00 Zenon said good night, and we finished the evening in the excellent company of Martine and Blork, talking about moving, learning French, San Francisco, pizza...in other words, it was a fine night and a happy first meeting.

5:01 PM

|

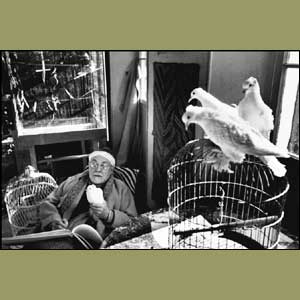

MORE CARTIER-BRESSON

For a brief overview, see this expanded group from the BBC. The first image is the one we had in our house, and it's one that's often used to illustrated C-B's phrase "the decisive moment".

An in-depth retrospective has been put up on the Magnum site (be patient, the site is slow to load). Magnum was the first organized photographic agency (Cartier-Bresson was one of the founderf) and remains one of the best and most prestigious photojournalistic organizations. the organization was also a pioneer in protecting artistic copyright and raising the level of regard for editorial and journalistic photography as a profession.

A few years ago, we saw a Cartier-Bresson retrospective. I had never seen his photographs from Mexico and China and Russia in a group, and I remember being stunned by the humanity in every shot. There was nothing sensational or grabby in his work, and you never felt like either the subject or the viewer was being manipulated or exploited. They were records of moments in human lives, where the subjects were not judged or labeled or ranked. I can't express it exactly. I simply always felt with Cartier-Bresson, the humanity of each person was elevated by his own humanity, his own anonymity even though, in real life, he was far from anonymous. But when he took his pictures, I am sure there was no sense of personal celebrity, rather an identification with all people and a desire to be an eye, not an ego.

10:28 AM

|

Wednesday, August 04, 2004

HENRI MATISSE, by HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON

It's necessary to interrupt this travelogue to pay tribute to Henri Cartier-Bresson, who died today at age 95. The picture above is from a short article about the photographer, with some images, at the BBC. I was surprised to see the announcement of his death this afternoon because, frankly, I thought he had died a while ago, so great was his reclusiveness.

My husband, J., who is a photographer, always admired Cartier-Bresson. For years a poster with one of his famous images hung in our house, and we have often taken down one of the books of his work and pored over it. J. likes and practices the genre known as "street photography" more than any other. I don't know if Cartier-Bresson, the renowned Magnum photo-journalist, Parisian legend, and photographer of luminaries, could be said to have "invented" street photography but he was certainly a practitioner and his work paved the way for the many fabulous street photographers who followed. He coined the phrase "the decisive moment" and his best work is an illustration of that concept - one which I think a Zen master would recognize.

From what I've read, Cartier-Bresson was still taking photographs at 95, but preferred anonymity to fame. Farewell to one of the truly great artists of the 20th century, from whom I have learned a great deal about creativity and spontaneity underpinned by technique.

3:40 PM

|

Tuesday, August 03, 2004

LUNCH COUNTER, RUTLAND, VERMONT

On Friday, we headed to central New York State to attend a family wedding and visit my parents. We were in Rutland, Vermont around lunchtime, and so we stopped at the Seward Family Restaurant, a favorite of ours, discovered from visits to the Rutland Fair, a true rural fair with vegetable exhibits, livestock judging and ox-pulls.

It's a family-style diner, with tables as well as a lunch counter, and the whole thing has grown up around one of the last working dairies in the state. I think you can still go through the restaurant and through the gift shop which sells maple sugar candy and syrup and Vermont t-shirts and the ubiquitous cards and calendars with autumn leaves and cows and covered bridges, to look in on the actual dairy with its stainless steel tanks and pipes and butter-churns and ice-cream machines. We didn't do that this time, nor did we eat ice cream, just the chowder of the day - corn - and a turkey sandwich. The waitresses were all elderly women, and the people at the next table were a Vermont couple, clearly in their late eighties at least, the woman in a flowered housedress and the man in a cap from a tractor manufacturer. It's the sort of place where men leave their hats on, and kids can, and do, run around from table to table.

That's Mr. Seward, in the framed photograph, taken back in the fifties, when Vermont was really a place where there were more cows than people, and nobody would have argued,as they do now, that the Rutland Fair wasn't important anymore.

3:16 PM

|

|

|