Thursday, July 29, 2004

BRIEF HIATUS

Blogging will be spotty over the next few days; we're driving tomorrow to see my parents, attend a family wedding, and then go back to Canada via an entirely new route! Very exciting. Report and pictures to come.

8:12 PM

|

Wednesday, July 28, 2004

A few days ago, I wrote about a wide-ranging conversation with a Montreal salesman. What I said was, unfortunately, misinterpreted as disrespectful by a few readers, and I want to try to explain my position better than I perhaps did originally.

In northeastern America, where I have spent nearly all my fifty years of life, we have, to a fairly large extent, a hierarchical society, where people tend to make assumptions about a person's educational level, political opinions, and even lifestyle choices based on their occupation (as well as various other "clues", such as dress.) These categorizations are true often enough to allow people to fall into the trap of stereotyping people. When I go for an appointment at the nearby medical center, I will have a different sort of exchange with the doctor if I wear "professional" clothes rather than jeans. I have a friend who is a stay-at-home mother who deeply resents the fact that she isn't taken seriously by the local university-professor crowd, even though she holds a PhD in English Lit from a prestigious university. I'm sure we all have our own examples; maybe we have even been in that position ourselves. I certainly have been, and it feels rotten.

What I have noticed in Canada is that it seems to be a flatter society. What I mean by that is that there is less economic stratification: fewer people at the top, fewer people at the bottom of the class ladder, and more in the middle. Three times now I have had extended conversations with people in professions that here are, 90% of the time, occupied by people with, say, a high school diploma, yet in Canada they were clearly as educated, as well informed, and as articulate as you'd expect from a US college graduate, and feeling no stigma whatsoever about their choice of profession. This may imply something about differences in basic education, or in pay scales for various professions, or it may mean that people don't care about such distinctions there, or have different economic and social expectations. I could also be wrong, but with more money spent in Canada on social programs, it does seem to be true that a decent lifestyle is within the reach of a larger percentage of the population. (And since qualifications seem to be in order, that doesn't mean there aren't highly educated, articulate, informed people in the US who don't have college degrees, and I don't mean to imply that.)

When we're privileged to move between societies, we see differences, and we see our own in a new light. The things that surprise us point out something for us, hold up a mirror. The fact that I am still startled when I see interracial couples holdings hands as they walk down the street in Montreal doesn't mean I am prejudiced against them - on the contrary. It means simply that interracial couples are not often seen where I have lived before, and so it takes me by surprise. The fact that I was surprised by the conversation with the salesperson doesn't mean that I think all salesmen are uneducated, it means that the people I have known in his particular profession were very different sorts of people in my part of the United States. I don't go into a restaurant and "assume" that the waiters are somehow "beneath me", and I think anyone who has read this blog over a long period of time would realize just the opposite. What I was trying to do was point out some apparent differences between societies, and obviously I didn't do that with sufficient clarity.

How do we talk about "difference" without making an occasional generality, even with the hope that it will be challenged by those who may know the exceptions to which we have not been privy? I neither want to offend, nor be misunderstood; how ironic that a post about prejudice should be seen as prejudicial!

But the larger issue here is not what I said or felt in this particular instance, but the question of what makes a workable society where most people have a sense of self-worth and value. What do we do, as members of a society, to affirm or deny a person's value, or to truly and sincerely meet one another as two equally precious, worthwhile human beings, in all our mystery? I am involved in a life experiment where many of the former "clues" don't work. This gives the possibility of even greater misunderstanding and misinterpretation, but it also opens the door to meeting others, and being met, on a new basis, using different methods of communicating identity and the desire for contact and connection.

9:04 PM

|

Monday, July 26, 2004

CANNAS on the street

In yesterday’s comments, Peter wrote:

Years ago when I was trying to embed myself in the northern Catskills, indignant locals regularly told me tales about insistent or impatient New Yorkers who had gotten under their skins. I never figured out whether they were trying to justify a stereotype or just expressing frustration. I guess you haven't met any similar prejudices -- could it be because rue Mont Royal is experienced in meeting outsiders?

There is definite resistance in Quebec, and in the Plateau Montreal, the historically French area of Montreal that I'm living in, to any forces that could contribute to the dilution or eradication of French culture. The Quebecois are pretty fierce about this, and they are right to have those fears, because it is gradually happening, for a variety of reasons. More than one native person has said to us, sadly, “French culture in Quebec will eventually disappear, mainly because children don’t want to speak French, they want to be like the prevailing culture they see in the movies and on TV.”

When you read the papers or see locally-made films, it's clear that Anglos (their name, not mine) moving into the Plateau because it has "cachet" are, to some extent, resented, but at the same time Quebec society has an underlying tolerance of diversity, and acceptance of the inevitability of change and the need for a stronger economy. As in so many other places, the influx of “foreigners” with the money to pay for what they want drives up housing prices and forces the less-affluent local citizens out. On the streets I walk here everyday, I see constant evidence of this tension: old buildings that have been expensively renovated, next to original ones occupied by, for example, an old couple who spend their afternoon out on their simple balcony reading the paper and tending their window boxes. I don’t know what percentage of the new residents speak French, although many do. Clearly, we represent part of this whole dynamic, which is familiar to me from Vermont’s struggles to deal with “flatlanders” – the local name for immigrants from Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York and New Jersey – who are attracted by the local culture and landscape but bring their own values and expectations, eventually changing it forever.

The political issue of Quebec separation is still alive, viewed as a dream or a threat depending where you stand. And with or without a separate Quebec, the political party Bloc Quebecois is committed to representing Quebec interests in the national government. The more subtle aspects of this issue are too complicated for me to fully understand yet, and I certainly can't address them here. One fact is for sure: candidates for the Bloc Quebecois swept this part of the city and won 2/3 of the seats in Quebec in the last election. The party won many seats that had been predicted to go to the Liberal Party. In Westmount, on the English side of Montreal, Liberals won by a large majority. But the Conservatives, who were feared because they had a more conservative social agenda and foreign policy ideas more conciliatory to Washington, were trounced in Quebec.

Personally, I haven't seen evidence of these issues so much in public places, like stores, but the first question various neighbors asked, after saying "welcome", was "do you speak any French?" (The word seemed to have gone around the building that "they're Americans but they're very nice and she speaks a little French"). When I assure them yes, a little, and that I'm trying hard to improve, there is a definite relaxation. If you are trying to fit in, and express an appreciation of the culture that exists here, and don't bring rampaging American culture, speed, and consumerism - the "Toronto effect" - I think you'll be tolerated and eventually accepted. I hope so.

One day when I was out on the terrace tending my own flowers, and talking to a neighbor, an old man came by and started asking me questions in rapid French. He had a craggy, kind face; light blue liquid eyes; and was wearing a short-sleeved plaid shirt. I understood that he was asking me something about this building, which is about twenty years old – how long had it been here, did I know what was here before? – but I couldn’t understand enough to make an intelligent reply. My neighbor did, though, and I heard her say to him, gently and sympathetically, “That’s the way of the world, you know, everything changes.” He smiled at us both, but walked away with hunched shoulders, shaking his head. That was the most painful thing that has happened to me here, and I know it will stay in my memory and be an incentive to my language-learning and also remind me to be as sensitive as I can.

Maybe some of the Montreal (and Canadian, in general) readers of this blog would be willing to add their perspectives and correct anything I've said that's not accurate...

10:36 AM

|

Saturday, July 24, 2004

LATE AFTERNOON SHOPPING SHADOW

Every time I go shopping here, I know I am letting myself in for feeling awkward. And it’s strange to feel awkward, because I’ve spent thirty years in exactly the same place, knowing what to do where, and my entire lifetime in a culture that is fairly homogenous, thanks to franchising and television and transient people. That’s what we want, isn’t it? Go into a McDonald’s anywhere in the U.S., and a predictable experience will be delivered up – you won’t even have to ask anyone where the bathrooms are. My father-in-law told me about a book, a privately published memoir written by one of his neighbors who had recently moved to the same retirement home. It tells of a trip around the world. “But,” my father-in-law confided, “they didn’t really see the world – not the way it really is. They were staying in grand hotels, eating familiar food.” He knows; all his traveling has been done the other way.

The last time I remember feeling this awkward was when I went away to college and didn’t know where anything was or how to do things so that I wouldn’t make mistakes. Back then, at eighteen, the last thing I wanted to do was have attention drawn to myself, so I remember cringing at every new, unfamiliar experience. I guess I’ve changed a bit since then. Now, each trip out my door is an adventure, and the awkwardness merely amuses me – in fact, I like it because it tells me to notice and think about all these differences that are tripping me up.

Doors, for instance. My shopping takes place mostly on rue Mont Royal, which, in addition to being considered one of the hip streets of this city, caters to the needs of the local residents of the Plateau Mont Royal, the area in which we are now living. For someone like me, setting up a new place to live, there are hardware stores, dollar stores, kitchen stores of the cheap or expensive varieties, pharmacies, supermarkets, laundries and dry cleaners, and many wonderful specialty stores selling meat, cheese, fish, coffee, chocolates, breads and pastries. Of course, there are also stores selling books, CDs, furniture, flowers, clothes, shoes, lingerie, fabric, gifts…you name it…as well as many, many restaurants of every possible ethnicity. By New York standards, none of this is "fancy"; Avenue Mont Royal is not SoHo, at least not Soho of the last twenty years. Some of what's here is trendy, to be sure. Mainly it's fun, and varied, and, like most of this city, casual. When I first started coming here, I thought rue Mont Royal was, well, touristy. What I didn’t see then, and am just starting to understand now, is how the tourist shops and restaurants co-exist with all the purveyors essential to a thriving local, neighborhood economy.

But back to doors. Lots of stores here have an entrance door, and an exit door. This is not the same where I come from: most of the time you go in and out the same door. Every single food store I’ve visited is set up differently, and now that I’ve finally figured out to look for the entrance door, I am beginning to avoid walking into the cashiers instead of the lane where I can pick up a basket or cart. Sometimes there is a turnstile, sometimes not. That gets me into the store. Now I have to find my way around it. Supermarkets are easy, because they are mostly self-serve, as in America. But this is neighborhood shopping, with real butchers and bakers and fish mongers who expect to wait on you, so you have to learn how to ask for what you want. Then you have to figure out how and where to pay. In some boutique-style stores, you pay at the department – meat, or cheese, for instance. In most you pay at the cashier up front, where they will invariable ask, in French, some question like “Do you want to pay for the exact amount or would you like cash?” or “Do you have a store charge card?” Everyone switches to English instantly when I look bewildered, but I want to learn the French phrases so sometimes I ask them to repeat what they said. It is all very friendly, and the people in line are patient with each other – I haven’t received one dirty look yet. The final task is to learn where to leave your basket, and where to exit the store. And then remember it all the next time you go there.

I mention this because it is so amazing to me to realize how much of daily life I have taken absolutely for granted, and how terribly difficult moving must be for people who immigrate from entirely different cultures, often without the benefit of local language skills. The disorientation must be staggering. Even for us, making all these small adjustments to a new place has a physical effect; we are both feeling clumsy, we drop things, bump into things, forget things because our bodies are not used to moving in this space and our minds have not yet learned new patterns. It’s an eerie feeling, difficult when you fight it, but fascinating when you just let go and ride along, watching your body and mind discover, adjust, learn.

7:08 PM

|

Thursday, July 22, 2004

VACUUM ZOOM

Before we came up here with the van, we went shopping for a new vacuum cleaner. With the latest Consumer Reports ratings all printed out and in hand, we arrived at the correct aisle in the local Sears and were greeted by Stacey, a young, skinny, dark-haired, quite pregnant woman with sallow skin and a wry smile. Stacey, it turned out, knew her vacuum cleaners, and she was also ready for Consumer Reports types like us.

We hadn’t shopped for vacuum cleaners for at least twenty years, not unlike our recent forays into mattress-land, but vacuum cleaners had obviously changed a good deal more. First of all, they were huge, and second, they looked like spaceships. “Wow, this is really heavy!” I exclaimed, hefting a streamlined purple model onto the floor as Stacey stood by sympathetically.

“Yeah, they’ve gotten pretty fancy,” she commiserated. “But they kind of propel themselves. See, this is all plugged in, you can try it.”

Whoosh…the vacuum cleaner practically leapt into action. “What’s this?” I asked, pointing at a red light that flashed green as I guided the self-propelled vacuum across the floor.

“That’s your dirt sensor,” said Stacey, looking at me almost apologetically – she already has us pegged, I thought. “It senses where there’s dirt in the carpet, and changes to green when it’s clean.”

“Oh, really!” I said. “Honey, did you see this?” J. had been over in air conditioners, and he came to meet me.

“What have you found out?” he asked, and then, looking at the row of poised futuristic monsters in front of me, “What are these?”

“Vacuum cleaners. Look, this one is rated a Best Buy.”

“You’ve got to be kidding,” he said. “Where are we going to keep it?”

“Beats me.”

“What does it eat?” he asked. Stacey looked on, pretty patiently I thought.

Finally we selected a cheap model that was lighter, smaller, and bagless. We also bought the least expensive microwave they had, for the close-out price of $26. None were in stock, but Stacey sold us the display model off the floor, assuring us that she’d have an instruction manual sent to our home. I hope she does, because it’s on the counter here in Montreal and I can’t figure out how to set the clock. We took the vacuum cleaner home and tried it out on our rugs and on the bare floor, and to our chagrin, it cleaned far better than the old one. The “turbo tool” did a fast job on upholstery, and having a hose and nozzle attached to the upright vacuum cleaner was a lot more convenient. What was gross though, was the see-through plastic container that replaces the bag – all the dirt, grime, dustballs, seeds, and pebbles in the carpet were now quickly accumulating. I thought it was funny; J. thought it was disgusting. He does the floors, though, and what really mattered to him was that they were cleaner.

The next day he went out and bought another one to replace our two old vacuum cleaners, one upright and one canister, which suddenly looked like relics from the dark ages. The lighter model from Sears came with us up here, and the other one – purple, with a real bag and a headlight, in case you’re vacuuming away your insomnia – awaits us back in earthy, futuristic Vermont.

10:05 PM

|

Wednesday, July 21, 2004

Last night we arrived late, unpacked the car, and slept on our new mattress instead of the sofa bed – on the floor, but hey, that’s fine – and woke up to a beautiful morning in the city. It’s been very hot, but not too oppressive, and we’ve been glad to find out that our apartment stays pretty cool if we keep a fan running.

This afternoon we had a long conversation with a native Frenchman who has lived here for thirty years. He works in a sales job in a service industry, and came to our apartment exactly on time for the appointment we had set up. As it turned out, he was not only competent and professional, but well educated, very informed and thoughtful about society, politic, and foreign affairs. In case I need to say it, we were taken by surprise: once again, a social encounter pointed out how quick we are to categorize people, how much this seems to be an American trait, and how wrong those categorizations tend to be here.

He wanted to talk, as several people have, about America post-9/11, and to find out whether his perception was really true that our society has become much more fearful and willing to trade illusions of security for civil rights and personal freedoms, something he felt very sad about. He also wanted to compare the two societies on values, especially attitudes toward gun control and materialism. Since his parents still live in France, he was able to speak about French attitudes too, and it was most interesting. “One thing we cannot understand here, and the French cannot either,” he said, “is how America reacted so dramatically to the horror of the deaths on 9/11, but every year there are – what, ten times that many? - people killed by guns in the United States. This doesn’t make any sense to us.” He looked closely to make sure he wasn’t offending us. “As you can see,” he said, ‘I feel comfortable with you, so I can talk like this.” He went on: “Sometimes, it seems to me, having personal freedom to that extent becomes not-freedom; it becomes like a prison. To be so afraid, to live with fear of violence, to not be able to walk on the streets at night – this would be intolerable to me.”

We had concluded our business forty-five minutes earlier, and now we sat and talked while the breeze blew in the window and bicyclists sped past on the street. Our guest kept apologizing for his English, which was accented but nearly perfect; in spite of the fact that he was expressing very abstract ideas he said he felt like he was speaking “as a child”. We talked about quality of life, and about food, and ethnicity, and tolerance and what it means, and then we spoke a little about the Iraq war and European and Canadian attitudes. “Here in Canada, we see ourselves as being in-between Europe and the U.S.; both are our friends, we have reasons to care about both. Some Canadians will say, ‘We don’t like the U.S.’ but it’s not really true. The same with the French. The French love America, and always have. That’s why Chirac was able to say what he did. This is how you are with a good and close friend. You can say, ‘I love you, but I disagree with the thing that you did, or the way you are behaving, and because we are good friends I feel I can tell you honestly.’ It’s true, though, that a lot of people don’t feel quite the same way about America as they did before 9/11, and those relationships will have to be rebuilt.” He insisted, even when we expressed some pessimism and frustration on the point, that Americans were unique in their ability to be self-critical and to change. “It’s one of the strongest things about your society,” he said, “and one that the rest of us admire very much.”

He was optimistic, forgiving, and philosophical. I said I thought perhaps America was like an adolescent, and that we didn’t have the maturity yet to make wise decisions. “I don’t think it is a question of maturity,” he said. “All great powers are tested this way, and they all make big mistakes. The question is whether we learn from them. And really, when you look at it, all our recent story – say, the past fifty years - all of this is just a blink of an eye. We can be very critical, but we also have to look at the things that have improved so much, like the advances in medicine. So science has progressed a lot, we have better health, now we need to take that to Africa. But we don’t – we’re not there yet. Hopefully we will be someday. This is how the world moves forward. I can envision a world that is full of peace where everyone is taken care of. I can see that in my mind. But we are not there yet. It’s a slow progression.”

I had told him earlier that I was a writer, and J. was a photographer. “What do you write about?” he asked. “I often write about religion,” I said, now looking closely at him to see his reaction, but there was none.

But after his comments about politics and society, he said, “I think God has given each one of us a candlelight that is burning inside.” He tapped his chest with two fingers, and his eyes became soft as he looked directly into mine. “Sometimes you lose the sense that it is still burning, but actually it is. Each of us has to guard that light, which is a gift to us; that is what I think.”

“That’s why I write about religion,” I said, smiling, and he smiled back while J. laughed in agreement.

“Yes! And I have stayed a long time.” He got up and shook both our hands, very formally. We thanked him and said how friendly and helpful nearly all of the Canadians have been that we’ve met.

“May I tell you something?” he said, and the question was a sincere request for permission. We nodded and said of course. “Many friends who have come from France to live here have told me this. They say that the Quebecois are very, very friendly, and warm, and helpful, and that they met many people like this. But it takes a long time to make deep, lasting friendships here. That is what they say, and I think it is true. Perhaps it will help you to know that.”

He walked toward the door and turned back. “It has been very good talking to you. If you need any information or help about things here, please call me.” The door shut behind him, and we sank onto our couch and looked at each other, once again astonished.

9:44 PM

|

Monday, July 19, 2004

FLAT.

As soon as you get above Vermont's Green Mountains, the landscape flattens like a lump of butter melting onto a griddle, and it stays flat all the way to the St. Lawrence. It's hard to believe the degree of change, when you've just passed through pretty tall mountains. It's also hard to imagine the amount of corn that is being grown in these fields that stretch from horizon to horizon, and, in the warm summer, to remember the fierce and frigid wind that blows incessantly from the northwest all winter. But this is the season of mais sucre, sweet corn, and strawberries, whose images - with eyes, teeth, and legs - adorn signs all along the road. We stopped and bought four ears of corn, two cucumbers right off the vine, a little container of fresh red raspberries, and a handful of the biggest, meatiest cerises - cherries - I've ever seen or eaten - not grown there, I'm sure, but amazing.

We drove a rental van with some furniture and household items to Montreal on Saturday, and came back late Sunday night - a long, hot 36 hours with a lot of lifting and hauling, a morning trip to IKEA (had to take advantage of that van while we had it), and a long hike from the Plateau to downtown in the baking heat of yeserday afternoon to pick up our DSL modem (first things first, after all!) Then I came back and worked on the little garden on the terrace for the rest of the afternoon while J. got the DSL working - somewhat. Now we're back in Vermont.

It's funny - there were a lot of compliments on my garden pictures, but I was just as absorbed and interested trying to figure out what to do with the little shady terrace outside our city apartment. I think a garden is a state of mind: one can have a garden anywhere - even in a single pot outside a window, and that little place can transform one's approach to the world. My father-in-law now has two gardens. One is the orchid plant he rescued from a retirement-home cast-off bin, and is nursing back to health in his bedroom. The other is in an assortment of pots on his balcony: radishes, a cherry tomato plant, a pot of green onions, some zinnias, a rose-scented geranium, a window-box full of parsley. There is a hummingbird feeder, and everytime we visit him he insists on an inspection of his garden and tells us how he sits there in the evenings and watches the hummingbirds, and all is right with the world.

I'll post a picture of the Montreal "garden" soon: this time I moved the sun-loving plants to a better location, repotted the hibiscus trees, planted a pot of basil and parsley (known sometimes as the family vegetable), and put some coleus in the shadiest spots. Right now it's a learning time, to see how the sun moves and the rain falls, where the wind is damaging and where the plants are protected, how the plants could be arranged to make the nicest environment and "outdoor room" for people. But I've gone from feeling garden-bereft there to realizing it is mine for the making.

I'll also post, someday soon, a plan and picture of the whole garden here. When you see close-ups you will discover it isn't so glorious after all, and realize with me that it is too big and too much work for one small female with an achy back. One option is to stop growing all but a few vegetables. Another is to move toward more shrubs and fewer perennials in some of the difficult locations. More abstractly, this relocation and restructuring of our life is teaching me a lot about gardening: what it means to me, why I do it, which aspects are the most satisfying, when and how it becomes a burden. The city place is showing me that small can be good, too; re-assessing this country garden teaches me that much of what I call "home" is the instinct to care for something and to create a place that feels calm and beautiful, but that I tend to expand my ideas beyond reasonable bounds of what I can actually manage. Both gardens tell me that perfection is impossible when one is dealing with living things; letting go of that notion is essential to realizing the calmness the gardens were meant for in the first place.

12:52 PM

|

Thursday, July 15, 2004

MY JULY GARDEN

If anyone has any doubts about why it's nice to live here in the summer, this picture should set them at rest. Of course you have to add in mosquitoes on your arms, slugs under your bare toes, humidity, unpredictable weather and a short growing season, but midsummer in New England is pretty special. We came home to an explosion of hollyhocks - from yellow and pale pink to rose, maroon, and nearly black - I've never had such a crop. They make up for the dismal failure of most of my vegetables, neglected during the trips to Canada: the French beans, usually so reliable, are down to a third of the plants (slugs ate them); the carrots didn't come up; and the lettuce, tomatoes, and Swiss chard are late. But no woodchucks this year, and the neighbor's dog has learned to stay in his own yard.

Today I had to drive south on an errand, to a town that used to house highly successful tool-and-die industries and is now depressed. After completing my errand I stopped at the local Friendly's, ordered a BLT and coffee, and sat looking out the window at the shopping center parking lot, watching the people, listening to the conversations around me, and thinking of Tom Montag, who does this sort of thing a lot. I had to wait a long time for my meal. The waitress, a sturdy middle-aged woman with dyed blond hair and a worried expression, was running ragged, and came by twice to apologize for making me wait. The ice cream counter and cash register were being taken care of by an older woman, frail and slight but kindly, and much calmer than her co-worker. Behind me, a table full of men on their lunch break bantered about car racing, and a lone young man, wearing a reflective acid-green highway vest and a baseball hat, came in to pick up a take out order, slumping down in a seat by the window to idly read through the ice cream treat menu and soak up some of the air conditioning.

This part of the state is very different from where I live; it's far from universities or stable employment, but it is also closer to the way things used to be. The people are solid, kind, and hard-working when there is work; the young girls - of whom several showed up to go to work on the afternoon shift - are wholesome, tending toward the strong-and-hefty, with fresh complexions and guileless faces. A generation ago, they'd be milking cows. Now they're making milk shakes at Friendly's, or packing groceries at the local supermarket.

Thanks to some foresight and an excellent town planner, this particular town has started to come back from the exodus of the tool-and-die industry, and it's also managing to preserve its downtown. After lunch I drove slowly out of town, and stopped at a farm truck with a canopy parked alongside the road and bought two pounds of fresh peas in the shell, a zucchini still dewy from the morning when it was picked, and a couple of ripe, perfect tomatoes from a friendly, buxom woman with eyes that went in separate directions. Then I drove home through sun, a sudden rain shower, and sun again, listening to an old Rod Stewart tape, singing along and playing the steering wheel like a drum.

4:45 PM

|

Tuesday, July 13, 2004

NEIGHBORHOOD ERRANDS

We're going back south today, and I had a number of errands to do before we left. Early in the morning I went on a croissant-and-baguette run to the best nearby bakery, about four blocks from here. It's a lovely walk, along the park and narrow streets where everyone's little garden is bursting with color and individuality. The bakery itself is a room about the size of our terrace, with croissants and pastries displayed in the window, baskets of freshly-baked baguettes on end, a counter for the cremes glaces that are the nightime allure of this place, a small, lighted display case for tarts and cakes, and another refrigerated glass case, near the cash register, filled with excellent cheeses and pates in little porcelain ramekins. Clearly, we have only just begun to make the acquaintance of this boulangerie and its offerings, but the baguette was the best we've had so far, and the croissants, eaten on the terrace with our morning coffee, were buttery and flaky and, in my estimation, nearly perfect.

Then it was back to setting this place in order, knocking down the plethora of IKEA boxes for recycling, watering plants, cleaning the kitchen, figuring out what I could make for unch out of the leftovers in the refrigerator. Then I went toward the main street to do three errands - go to the bank, the locksmith, and the fishmonger.

In this quartier, French is the language, and nearly only French. Left you think everything about coming here is croissants and chevre, there are other aspects that I have found disorienting and dismaying, not the last of which is simply finding oneself in a totally different culture, not as a tourist anymore, but as someone who intends to stay and try to fit in. It is a completely different experience and mindset, and not being fluent in the language that everyone is speaking is much more of a strain than I thought it would be at first. At the locksmith, a small neighborhood shop, like most of these, run by a French Canadian proprietor who has probably worked there his entire life, I was able to ask for three sets of keys copied from the ones I presented. He replied, in French, "Three of each." I said yes. Then he said, "For a total of nine." I thought a minute, because he had used a verb I didn't immediately know, and said, "Yes, that's right." Then the phone rang, twice in quick succession. He turned to me, as he was making my keys, and smiled and complained that the phone wouldn't stop ringing. I smiled and said, "Yes," and that was the end of the conversation, because I couldn't chatter anything back the way I would have done so easily in English. It was the strangest feeling, and as I watched him make the keys, studying his face in profile and the type of shirt he was wearing, and the sort of shop he had - old, and filled with locks and keys and lock sets of every type - I was getting a feeling for the sort of person he was, and wanting to be friendly, but feeling the distance of the communication barrier like a flush suffusing my body. I wondered how long it would take. It wasn't that I felt American, or stupid, or foreign, or different, or like I couldn't communicate who I was by the way I smiled or gestured - I just felt that distance sinking in more keenly than I have before. "Voila, Madame," he said, putting the keys in my hand. "Merci," I said, and left.

At the bank, everyone was bilingual, and there was no problem, just more ethnic diversity: the officer who helped me had a Muslim name that included "Sayed", which means a family descended from Prophet Mohammad. Her dark eyes and hair that made me think she was Iranian, so - I've learned by now that this question is perfectly OK - I asked if she was. No, she smiled, she was Lebanese. We talked a little, and I told her my husband's background. "But your family name..." she said, quizzically. "No, he has a different name," I said (mine is as Anglo as they get), and we both laughed. Different names for husband and wife are common; every couple in our building uses different ones.

The final errand was at the poissonerie, just two blocks from home. I've been studying a beautiful fish cookbook, a very thoughtful house-warming present from our Icelandic neighbors who knew I was looking forward to exploring a much broader range of fish species and cookery than I've ever had access to before. I had memorized the French names for halibut and haddock, the two fish I was looking for, and so when I walked into the shop, a concrete-floored room with a freezer case on one side and two long glass cases, packed with ice, and whole and cut fish, I was able to read the signs and be sure I was asking for the right thing - although halibut and haddock are pretty clearly themselves. "Je voudrais d'eglefin," I said, and the proprietor came over and asked me how much I wanted. "Quatre fillets," I said, and he repeated the number, which made me realize I had pronounced the end of the word instead of leaving it silent. "Quatre," I repeated, more correctly, and held up four fingers. The proprietor, a thin man in his forties with a chiseled face, dark hair, and bright eyes, looked closely at me. "Do you speak English?" he asked. "Yes," I said. "So it's better this way," he said. "Yes, but I am really trying to improve," I said, probably looking helplessly at him. I liked him. He smiled. "It's easy," he said. "I had no...school...but I learned French and English just from talking to my friends. You will learn." "I have to practice," I said. "Yes, of course!" he shrugged, while weighing the fillets and putting them in a white opaque plastic bag. "What is your native language?" I asked. "Portugese," he said. "Oh!" I said, smiling again. "Well, you will be seeing me a lot. I've just moved in nearby, and I love to cook, and there are so many new kinds of fish here that I want to learn how to cook." "I can...explain for you," he said, and blushed ever so slightly. I smiled and said that would be wonderful. "It would be my pleasure," he said, in French.

4:38 PM

|

Monday, July 12, 2004

Thank you so much to all of you for your good wishes! I really do feel welcomed here, and encouraged, and it is much appreciated by both J. and me.

Ah! We've been working hard getting settled, and it has been tiring but also a lot of fun. J. and I have never really done this - we combined our two small households when we got together in 1979, and I moved into the house where he had been living. We've never left. So we've simply accumulated and sifted and rearranged, assimilating household gifts and occasional - but not many - purchases. The idea of starting almost from scratch, in a new structure rather than a century-old one in constant need of maintenance, is absolutely radical. And we are both still in a kind of disbelief at where we are finding ourselves, and the fact that everything in this apartment works.

In Canada, apparently, applicances are generally not left or even offered for sale in a house or apartment when the owner moves. So we had to find some. The prices of new appliances seemed pretty prohibitive to us, but within four or five blocks of here, there are probably twenty dealers in refurbished ones. So last week I set out to see what I could find. In the first shop, I was met by the owner, a large French Canadian man in dark green work clothes and thick glasses. "Oui, Madame, bonjour," he greeted me, and asked what I was looking for. "A stove and refrigerator, I said, in French, and then asked if I could speak English. "Non, Madame," he said, smoothly, "je parle francais seulement," and continued to chatter at me, barely taking a breath: "Here, Madame," leading me to a dented stove, "this one is very good, it has not very many years, very fine, also this one here, is this what you are looking for? You won't find a better one, only $250..." and on and on. The appliances were stacked together, chock-a-block, and they were all looking very old and very used. Monsieur Salesman was now shadowed by a gaggle of young men and boys who seemed to be family members and gad come out of the back of the shop, and every time he said, "Yes, Madame, this one is very good, a fine deal," they would all nod in agreement. I began to wonder if I was the only customer they had had all day. "Thank you, I'll come back with my husband," I told them, and backed out the door while the proprietor continued to tell me I'd never find better deals or a longer guarantee in all of Montreal.

A few doors down was another business, this one bright and airy, with the appliances arranged in long neat rows and good-looking, nearly-new samples in the window. I peered in, and saw the proprietor conferring with his salesman. They looked nice, and smiled at me - "bonjour, Madame" - as I walked in, but they left me alone and continued to talk. I took a quick tour and decided to plunge into conversation. "Je cherche un bon poele et frig," I said. "Oui, Madame," the proprietor said, and we continued, half in English, half in French, both of us switching back and forth as we needed words, although, as usual, he was much more fluent than I. (I find this sort of conversation wonderful: one of the most exhilarating and least predictable aspects of being here, and a situation in which I always learn something.) Eventually both the salesman and proprietor were involved, we were all having a good time, and I picked out a good-looking stove and refrigerator. I came back with J. an hour later, and we ended up buying a washer and dryer too, all for about $825 Canadian, with a two year guarantee on parts and three months on labor. An hour after that, they delivered and installed the appliances - and they all work just fine so far, except for one moment the first night, when the refrigerator made a screaming sound which finally stopped when we opened and shut the freezer door. The dryer was missing a handle on its door; today the proprietor called, as he'd promised, to say he had found one and we could pick it up - which we did. "Call me if the frig screams again," he said.

You know what this reminds me of? My home town, half a century ago.

9:19 PM

|

Sunday, July 11, 2004

HIBISCUS sur ma terrasse

After our arrival in the city Thursday morning, we picked up the keys to the apartment from the owner a few hours before the closing – he had offered this so that we wouldn’t have to leave our car, full of personal possessions, on the street. How kind! So we were able to carry our things into the apartment, change our clothes, and take a deep breath before going off to the office of the notaire on Avenue du Parc.

The legalities of buying a piece of real estate here are very different than in the U.S. For one thing, there is a special class of lawyers, called notaries (as opposed to avocats, but very different from the officials we call notaries in the U.S.) who handle property transactions. Both parties use the same notaire, and he or she is responsible for researching the title to the property, going back a number of years, pro-rating the taxes or other fees, and making up the legal contract for the sale. We only had one telephone call with the office of our notaire, telling us what to bring to the closing, and until yesterday we had never met her. As it turned out, our real estate agent, who normally accompanies the buyer to the closing, got caught in traffic and couldn’t make it. We were waiting in the reception area talking in French and English with the seller, who we have talked to several times and like very much. So after the phone call from the agent the three of us decided to simply proceed.

The notaire read all of the documents – there were not many - in French and translated them into English, with the rest of us breaking in occasionally to ask questions, often about various customs such as the tax code and the famous “welcome tax” that is levied on every property sale in Montreal. It was an entirely congenial meeting, about an hour long, with a lot of mutual translating, since none of us were completely at ease in the other languages, and ending with a discussion about Vermont and Quebec. We presented our check, paid the pro-rated taxes and condominium fees, everyone shook hands – and that was it. We had a quick lunch, got in the car, and drove back here, in somewhat of a daze that has still not completely lifted. Although we’ve begun to move in, and have slept here, and eaten several meals cooked in our own kitchen, it still feels quite unreal that this is a place we own now and can call home.

Everyone has been very kind – the former owner left two beautiful hibiscus trees on the terrace for us, as well as thoughtfully leaving soap, tissues, and toilet paper – and we have already met two of our neighbors, who were both friendly and welcoming. “Well, bienvenue,” said one man, a native of France, after asking what our schedule would be and finding out we planned to be here fairly often. “We are happy to have some Americans here in our building.” I smiled gratefully and thanked him, wondering if this was politeness or a true sentiment, but hoping very much that it was true.

When we were packing the car, we found we had some extra room, and both of us decided that what we really wanted to bring was some of our own artwork – a few of my paintings and several of J.’s framed photographs. They’re here now: a painting of a valley in upstate New York on the mantle; two photos from London leaning against a wall; a photograph from Vermont; a watercolor self-portrait of mine over the only piece of furniture we have here, a new sofa-bed. I thought it was interesting that this was what we wanted to have with us, beyond the essentials, and now they are reminding me that home has much to do with the creative spirit we carry with us, as well as other places, and other times in our lives.

Tomorrow: buying appliances en francais.

3:23 PM

|

Friday, July 09, 2004

We’re parked on Av. Peel at 10:30 on a foggy morning; J. has gone to the bank to pick up the certified check for the apartment and I’m staying in the car with our things. It is the city: people on bicycles; people with coffee; a big construction site right here next to the car with two orange cranes towering above the concrete, and construction workers with their hard hats and cigarettes amid piles of steel beneath a huge architect’s rendering of the eventual finished luxury apartments and retail shops.

Driving across the St. Lawrence on Pont Champlain this morning, the city grey on the far shore in its veil of fog, it would have been hard to encapsulate my feelings. I’m excited and nervous, but at center, relatively calm. I know this is a big step for us, and a major event in our lives – the beginning of something I can’t predict. We have set something in motion, and agreed to ride it without a sure destination. My calmness, I think, comes from knowing J. well enough, and myself well enough, to realize it’s not an irreversible decision. If it doesn’t work out, we’ll find something that does. I’m calm in the knowledge that I do love this place and am ready for a change and an adventure, which it will surely be – dealing with the language alone will be that.

What I found myself pondering as we crossed the wide, wide river, with the Stade Olympique in the distance and Maisonneuve’s “royal mountain” and cross ahead of us, is what will happen to me – to us – in this place. Will we continue to pass in and out of it, or eventually live here most of the time? How will it change me as a writer, and as a person? Who will we meet here? How will the city shape our work, our spirits? What can we contribute to its already-rich life? And how will it figure in the trajectory of these two human lives: will we someday grow old and die here, or will it be a place we live and leave, a stepping-stone on our journey through life? On this humid summer morning there are no answers, just the dampness curling the hair on my neck; the sound of metal clanging on metal; the workers’ appreciative glances at a passing woman’s derriere, and my amused appreciation of theirs; the traffic; the Tudor-style building on the corner with French signs – “á louer” “for rent” – on its black-and-white timber-frame façade. Bienvenue á Montreal.

4:26 PM

|

Wednesday, July 07, 2004

QUESTION

Have others had trouble lately accessing this site? One commenter says she has. I doubt I can do anything about it; I've had trouble accessing other Blogger sites this past week too, and it has taken ages to "publish" each post. One thing you can try if the page doesn't load and you get an error message - hit "GO". Sometimes the page will then come up. But please let me know if you've been having trouble.

11:17 AM

|

Tuesday, July 06, 2004

HOUSEKEEPING

We are packing the car to go to Montreal tomorrow, and will be closing on our new apartment on Thursday. One of the first things we'll be doing is installing a network in the new place, but please don't expect much blogging for the rest of the week. If my stats over the last few days are any indication, everyone's on vacation anyway!

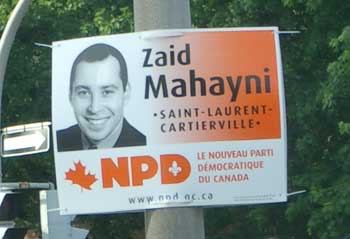

We became very interested in the recent Canadian election when the posters for the candidates went up during our stay there, about six weeks before the vote. I was so surprised to see posters for so many candidates with ethnic names - Indian, Arab, Greek, Asian and many others, in addition to the expected French-Canadian and English names. "How wonderful," I thought, "and how sad to notice the level of my surprise." We followed the election avidly, not knowing much of anything about how Canadian politics works or who the parties are. I still don't know enough to say anything about it, except that it was refreshing to see a multi-party system in action, and to hear national debate about both the electoral system and major issues that effect people's lives.

One of these days I will update my blgoroll to more accurately reflect what I'm reading. In the meantime, I'd like to recommend a few Canadian blogs that I enjoy. All of these blogs have eclectic, well-written, intelligent content, ranging from art to politics to international culture.

Marja-Leena, who I have mentioned before, is a talented Finnish-Canadian printmaker. She writes about art, culture, politics...and regularly posts some of her work, which is beautiful.

chandrasutra may be known to those of you in Buddhist circles, but the blog includes extremely thoughtful, intelligent commentary on Canadian politics and societal trends as well. Her recent posts on "Deep Integration" and on the Canadian elections should be interesting to anyone.

Flaschenpost is written by a German/Canadian woman in Vancouver. I've especially enjoyed her comparisons of German and Canadian politics and culture.

And Idle Words, by painter/programmer Maciej Ceglowski, is another take on a recent move to Montreal by someone who was living previously in Vermont. He's an excellent writer and observer, and often quite funny; take a look.

As for me, I'll see you all in a few days.

3:58 PM

|

Sunday, July 04, 2004

A PARTY

Yesterday we attended the 50th birthday party of a good friend who is a sculptor and jeweler. The party was a potluck barbeque held in a rustic pavilion at a large dam and public park, out in the country, which used to be a popular skinny-dipping site back in the hippie days around here. Now that the Army Corps of Engineers is in charge, you have to reserve the pavilion months in advance, promise not to consume alcohol on the premises (although there were margaritas in the lemonade containers), and keep your bathing suit on. By the time we arrived, the park ranger had already cruised by twice.

Most of the people who came were also involved in the arts in some way, and they hailed from Vermont and Manhattan, the two places our friend has lived. There were people we've known forever, and a lot of new faces, and since it was a pretty hot day, we all ended up sitting on picnic tables under the open pavilion, talking and eating grilled chicken and hamburgers and sausages, salads of every description, roasted corn, blueberry coffee cake and platters of brownies until the sun went down.

The talk was, not surprisingly, heavily political. This was a liberal crowd, many of whom had seen Michael Moore's film and wanted to talk about it, and there was a lot of speculation - and anxiety - about what would happen in the election. The New Yorkers wanted to know what attitudes were here, and vice versa. There was also plenty of typical artist chit-chat: "what are you working on, have you had a show recently, how is it going, I think I last saw your work five years ago..." with the most buzz about a young local sculptor who had had his first New York group show and immediately sold several works and been mentioned in a NY Times article. One of my old friends has just started a new commercial jewelry venture with a partner from Martha's Vineyard, so we heard about that and examined one of the prototypes, on her wrist; another has recently opened a fancy shoe store; and two Buddhists who have been together for eons told us that they had recently been quietly married. And as is always the case when Manhattanites are present, there was talk of inflated real estate prices in the city, and horror stories about trying to find apartments and studio space, and the usual, cathartic listing of advantages and disadvantages of living here (Vermont) and there (Manhattan) with the New Yorkers ending up satisfied that they were going back to where they wanted to be, and the Vermonters shaking their heads at the idea that it costs as much to keep a car in the city as some people live on up here.

I spent a long time talking to an elderly couple who I've known tangentially because they are film buffs who we often see at the movie theaters. The man, a former professor of creative writing, and I compared notes on films we'd seen recently. He's a typical local older person for here: crusty, amusingly dour, both self-deprecating and self-absorbed, a bit weather-beaten around his European features; he was attired in shorts, a worn polo shirt and an old khaki sunhat. I speared marinated green beans and roasted peppers from my plate of salad, eating standing up, and he talked.

Eventually the birthday girl came over and asked if we had everything we needed. Yes, we did, all except being fifty again, he said. She smiled and gave him a hug. "You're looking very pink today," she said. "Ruddy. Healthy."

"Well, you know what Emily Dickinson had to say about pink," he said, and recited in a clear, strong voice:

Oh give it Motion -- deck it sweet

With Artery and Vein --

Upon its fastened Lips lay words --

Affiance it again

To that Pink stranger we call Dust --

Acquainted more with that

Than with this horizontal one

That will not lift its Hat --

"She wrote that after studying a corpse," he said, turning to me. The birthday girl smiled politely and fled. "Every morning when I'm looking at my face in the mirror, shaving, I can't help but think of those lines."

Around seven people began to drift away, and we gathered our plastic containers, said our goodbyes, and drove home through the bucolic Vermont evening. When we first lived here, this outlying area was rural, still farmed, and the houses had often been owned by one family for generations. Now every one of these white clapboarded wooden buildings is worth at least three or four hundred thousand dollars, and owned by a doctor, or professor, or independently wealthy retiree. There's been an enormous amount of subdivision of former farmland, and construction of new, expensive homes.

But the land is beautiful, silent, inscrutable. Stone walls still wend their way through dark woods as if extending directly from the stone outcrops, covered with moss and limestone-loving ferns; above the fields and woods the mountains reign purple and blue in the distance, and wooly sheep still graze in the ditches beside the road.

9:32 PM

|

Saturday, July 03, 2004

Today, some recommendations. This ball, from a construction site in Montreal, reminded me of something qB might photograph. Since we're in mind of our buzzy lady from London, please bookmark the hilariously awful account of her day from last Wednesday, and re-read it whenever you are having a bad day yourself, as many of us seem to be enduring lately (what is it, anyway?? the moon? alien x-rays?)

I've just discovered a blog that I've been reading avidly, and want to recommend to you: it's called FunnyAccent and is written by a young Malaysian woman, named Anasalwa, living in Boston. She is a fine, sensitive writer, and her stories - and questions - will open up a new world and a new point of view for you. I haven't made my way through her archives, but I am looking forward to reading each post.

Finally, I think all of us who visit Creek Running North know that Chris is a very gifted writer as well as being enormously knowledgeable about science and the natural world. What is unique about him is the way he weaves both together. He recently wrote a post, following on the death of his grandmother, that reflects on the legacy of the women in his life. I'd have to place it at the top of my "Best of Chris" list; please find a quiet moment and go there and read it.

Happy Fourth tomorrow, everyone! Let's try to remember and celebrate the many things that are wonderful about our country.

5:07 PM

|

Friday, July 02, 2004

MALLOW

Conducting good interviews is a particular skill, one that I've come to appreciate much more now that I'm doing a lot, and trying to improve my own ability. I try to prepare as well as I can beforehand, both with background information and questions I'm planning to ask. I plan the timing and pacing of the interview, as much as I can: warm-up topics to try to get the subject comfortable with me, then a succession of more difficult ones, with breaks and opportunities to step back, relax, and reflect. I try to give the subject ample opportunity to talk about him- or herself freely - but some people don't like to do this. Then it's my job to draw them out. I like to have some questions they won't have anticipated, not in a let's-trip-them-up sense, but in order to try to elicit some less predictable responses. I tend to be hopelessly linear, but many people aren't. Often, I have to circle back, try a topic from a different point of view when a person has failed to answer a question. In almost every interview, there are also surprises - sometimes requiring that I abandon my "script" temporarily or totally, in order to go with a new, important direction. Being prepared for that is also part of the mix.

What I can't anticipate is how the subject is going to be feeling on that day. Wil they be focussed and sharp; eager; friendly? Or tired, distracted, even annoyed? People usually like me, but liking someone is different than trusting them. It's my job to try to quickly establish rapport and build trust, so that as the interview progresses, I can eventually ask the questions I most want answered and have a chance of getting an honest, direct response. Part of this is sensing how much to talk to a particular person myself, in order to reveal my approach and knowledge and sympathy, and how much to listen: 10/90? 30/70? Different people and circumstances seem to require a different balance.

I don't think I could have done this when I was younger. It takes all the inter-personal skills I've learned over my lifetime so far, and it also requires tremendous energy. I find I need a good night's sleep and razor-sharp intellectual focus during the interview, as well being keenly aware of body language and other signs of fatigue and annoyance, or enthusiasm for a particular thread of conversation. People change a lot from day to day, too, and what worked one day might not work on another occasion.

I especially like this aspect of my work, though, because it is so real-time, and so challenging on many levels. When J. is also talking pictures of the subject, during the interview, we work together to put them at ease so that they can forget the camera and just relax. Usually, we're successful, but as I review the session later, I'm often aware of things that worked and things that didn't. Each interview is an opportunity to hone my skills and improve for the next time.

Have any of you had experience in this field - either as interviewer or interviewee - that you'd like to share?

12:51 PM

|

|

|