Monday, September 29, 2003

"Form is Emptiness"

Hello everyone, and thanks for your comments and good wishes. I'm not on a trip or vacation, but living in and out of the hospital where my mother is recovering from major surgery. It's been an intense experience, but she is on the mend. I'll be back on these pages in the next few days; I've missed you all and missed reading your words in blogs and comments, but I'm also learning a lot of things I never knew about love and life.

4:21 PM

|

Tuesday, September 23, 2003

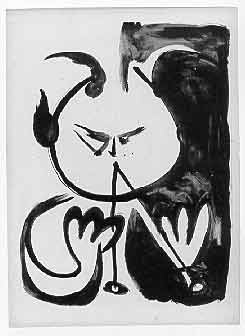

Pablo Picasso, Woman with a Flowered Bodice, lithograph

Today I got a nice note from a friend and fellow writer in England. He is a Buddhist, and we share that Buddhist/Christian mystic connection, as well as appreciating each other's writings on spiritual topics. At the bottom of his email were these three quotes, under the heading: "ON WRITING:" (thank you, M.)

"How necessary it is for monks to work in the fields, in the rain, in the sun, in the mud, in the clay, in the wind: these are our spiritual directors and our novice masters. They form our contemplation. They instill us with virtue. They make us as stable as the land we live on. You do not get that out of a typewriter." Merton

"Emerson considered it unnecessary that ' the writer should dig.'"

"It is my opinion that a man's soul may be buried and perish under a dung heap or in a furrow of the field, just as well as under a pile of money." Hawthorne

Interesting. I tend to agree with Merton, but realize that is personal and experiential - the clay and mud and wind teach me, and ground me, but they might be the wrong teachers for others. How about you?

A BRIEF PAUSE

There may be a pause in posts from Cassandra over the next few days; I'm going to be away on some family matters for a week or two and at first internet access will be spotty. Check in anyway, and I should be back online this weekend for sure. Books I'm taking with me:

The Courage to Be, Paul Tillich (almost finished)

Beyond Belief, Elaine Pagels (halfway)

Picasso and Matisse, Francoise Gilot

New Chinese Painting (artbook with a good looking text, on contemporary Chinese art)

The Road to San Giovanni, Italo Calvino

The Barbarian in the Garden, Zbigniew Herbert

AND, my knitting.

See you in a few days.

4:32 PM

|

Monday, September 22, 2003

My friend Shirin returned safely from Iran a few days ago. I missed her when she and her husband came over - I was at yesterday's Evensong - but when I walked in the door I knew who had been here: my desk was covered with packages with Farsi labels. Two little bags of precious saffron. Some sweets from Khazarun. Fruit leather - the very best kind, almost black and very thin. A big package of dried barberries, needed for many Iranian dishes. A bag of dried dill from the slopes near Shiraz - herbs from there are especially intense and fragrant. And a lovely little inlaid box with wood and mother-of-pearl cut in intricate patterns, and a scene of Persian horsemen painted on the lid. What a treasure, what lovely gifts!

"Moe" writes about the poem "Baran" on a website devoted to poetry by Iranians:

This is my favorite poem from my 4th grade Persian textook book. This gem of a poem by Golchin Gilani can still be found in today's textbooks and most school kids have it memorized as we did back then. The original poem is somewhat longer. We all need to be reminded from time to time of the uplifting finale:

Hear me O my child,

In the eyes of tomorrow, life --

at times dreary, at times bright --

is beautiful, is beautiful, is beautiful.

9:31 PM

|

Sunday, September 21, 2003

Thank you to everyone who wrote with birthday wishes. I was touched and surprised!

This afternoon I drove 35 miles south to participate in an Evensong. Fall is just coming, and as I drove I looked at the breathtaking scenery unfolding around each curve - the broad valley with the shining river, reflecting a blue sky and summery clouds, the incessant rhythm of soft round deciduous crowns marching up the slopes of the hills, and the first maple branches sending a shot of red against the sea of green.

Trinity Church is in a mill town, heavy with brick, but the church itself is white and seems small on the outside. Inside the church, built in 1840 or so, the afternoon light was soft against the creamy walls, and the central vault was high, airy, surprising. There were carved arches of dark heavy wood, the original box pews, hanging lanterns of wrought iron and glass, and narrow, arched stained glass windows running up each side of the sanctuary. The purpose of this Evensong was the dedication of a new window in memory of a woman who had been Eastern Orthodox, and the window, which was lovely, resembled an icon in style. It was also an occasion for the Bishop to address a gathered group of churches and clergy from one part of the Diocese.

Maybe only Anglicans can appreciate the beauty of Evensong on a clear afternoon in early autumn: the black and white robes, accented with red velvet, the sung Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, the sung Suffrages in old formal church language, the opportunity for a short but pertinent Homily (this time the Bishop preached on icons and how they represent incarnation, epiphany, and transcendence); the anthems by the choir; the fading light. We sometimes sing an Evensong during Lent with a Bach cantata as the musical centerpiece, but you often begin in darkness and end in night. Today the sun was only slightly lower at 5 when I left the church, and the red and gold of the sugar maples by the bandstand across from the church on the village green were merely more intense. I sat looking at the little park, the trees, the circling trffic, the people (mostly elderly) coming out of the church, the curious few young people in jeans and tee shirts on the park benches, wondering about the people in their funny robes - including me, probably, with my blue choir robe and red-ribboned oversize cross dangling from my arm. I sat still for a few minutes; it was like my childhood, and like right now, all at once.

In honor of the woman who had inspired the window, we sang the haunting Bogoroditsye dyevo by Rachmaninov. Listen.

10:19 PM

|

Saturday, September 20, 2003

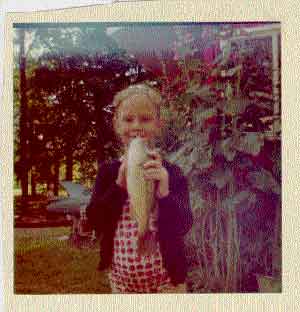

Cassandra with a Fish and Hollyhocks, c. 1958

It's my 51st birthday today. I don't think I've changed too much, really. I still grow hollyhocks but I don't fish anymore - I've gotten too tenderhearted in my old age - but that feels like me in the picture.

That was my grandparent's cabin on the lake where we spent summers, and where my parents still live. Our house was right next door. Grandpa was an avid fisherman, and often, in the evenings, he and I would work our way around the shoreline while the sun set. I carried a can of worms and a simple pole with hooks I baited myself; he cast with a red-and-white spinner. On other evenings my mother and I fished near "the perch tree", an old beech on the shoreline that hosted schools of perch in its shadows. I got good at feeling their sneaky nibbles, and once in a while actually caught one before it stole my worm.

There are few contemplative activities I like more than staring into still water. I spent many hours as a child lying face down on the end of the dock, gazing into the depths of the lake. Early in the morning we'd stand on the top of the bank overlooking the lake and be able to see fish swimming lazily among the weeds and submerged branches: sunfish, perch, large-mouth bass, sometimes a big carp. In the shallows near the sandbar we'd see pickerel, camouflaged like sticks, and small tender little bass, with their black stripe and tailfin.

In my dreams now, I often find myself staring into the lake. Sometimes there are fish, sometimes things that metamorphose fantastically into birds or dolphins, boats and flying machines. What do they mean, these dreams? I feel like my subconscious is under the water, swimming quietly, mysteriously; flashing silver; beckoning and elusive, but always familiar, always inseparable from who I am, whether or not I understand what it's trying to say.

8:25 PM

|

Friday, September 19, 2003

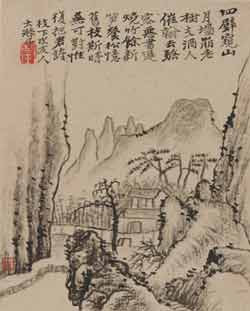

Reminiscences of Nanjing: Cliff-Bordered Moon, 1707, by Shitao. Freer/Sackler, Washington, D.C.

Returning to Fields and Gardens (II)

I plant beans below the southern hill:

there grasses flourish and bean sprouts are sparse.

At dawn I get up, clear out a growth of weeds,

then go back, leading the moon, a hoe over my shoulder.

Now the path is narrow, grasses and bushes are high.

Evening dew moistens my clothes;

bo so what if my clothes are wet -

I choose not to avoid anything that comes.

T'ao Ch'ien (365-427)

from The Silk Dragon, translations from the Chinese by Arthur Sze

10:32 PM

|

Thursday, September 18, 2003

GUINEA-ZILLA

From the journal Science, via the BBC:

Giant Rodent Astonishes Science

The fossil remains of a gigantic rodent that looked something like a monster guinea pig have been identified by scientists in Venezuela.

The 700-kilogram beast - about the size of a buffalo - lived among the reeds and grasses of an ancient river system that threaded its way into the Caribbean Sea eight million years ago.

Researchers think the creature, which was 10 times as big as today's largest rodents, could have run in huge packs.

Evidence suggests it also had to dodge the constant attentions of super-sized crocodiles and carnivorous birds, which stood three metres tall...

10:22 PM

|

Interior of St. Vibiana Cathedral, Los Angeles, 1945

HOLY SPACE

For those who enjoy good writing about "place", there is a beautiful article, "In the Shadow of Angels", in the "home" section of today's LA Times. Written by Marjorie Gellhorn Sa'adah, it is about living in the deconsecrated St. Vibiana Cathedral during this year, before the renovations begin that will turn the former 130-year old Catholic Cathedral of Los Angeles into a performing arts center.

...When I came to live here last year, there were still the dusty outlines of the Stations of the Cross running the length of the cathedral, but a film crew has since painted the walls and even those shadows are gone. The stained-glass windows have been removed, and clear daylight pours across the empty sanctuary onto the mosaic floor. Waves of earthen colors lap toward what remains of the marble floor...

The cathedral, rectory and gardens span the block just south of City Hall. Five of us — Lupe, Perri, Hal, Patrick and I — live in the rectory, in rooms that once belonged to priests and the cardinal. There are five floors with dozens of unused rooms; the rectory is a labyrinth of doors and hallways. You turn a corner and find yourself in a room with nothing but racks of old keys, a deserted dining room with impeccably hand-stitched curtains now gray with age, a wine cellar with rolled-up maps in the slanted racks. Let the wrong door shut behind you and you are locked in an enclosed courtyard with a gurgling fountain, overgrown fan palms, wild orchids and the sparrows.

(Getting onto the LA Times website is a pain, they have a lengthy registration procedure but you can sign up for a free 14-day trial and get in.)

8:53 AM

|

Wednesday, September 17, 2003

The discussion about words-creating-worlds has brought up the topic of the power of words, and there's some disagreement about when, exactly, words acquire their power - or if, in fact, words have any power at all separate from their human agents. There've been some astute comments pointing out that words themselves are not the beginning fo thoughts at all; that much of what exists exists in a space without labels, without concepts, without any projections of language, judgement, or personality.

Meditation teaches us a lot about the process by which thoughts, and eventually, words, form in our minds. Suppose I'm meditating and the neighbor's dog barks. What exists? Nothing has changed, really, but at the sound of the dog I may get a wave in my mind that, through a complex path, takes a form. It may go something like this: sound of dog/ mind identifies sound intuitively/mind labels sound: "dog"/mind places dog in context: "neighbor's dog, in back yard"/mind starts thinking and judging: "there's that dog again, it always bothers me when I'm meditating/damn, now I'm thinking, why can't my practice be any better than this, I'm so hopeless...

After we begin to perceive the complexity, we can begin to take it apart. The dog barks, we say to ourselves, "dog", or "thought" and calmly go back to our breathing. And eventually we barely hear the dog, or, perhaps more accurately, we hear it but it doesn't disturb us, so we don't go in the direction of labeling, associating, judging...

In the beginning the practice of meditation is just dealing with the basic neurosis of mind, the confused relationship between yourself and your projections, your relationship to thoughts. When a person is able to see the simplicity of the technique without any special attitude toward it, he is then able to relate himself with his thought pattern as well. He begins to see thoughts as simple phenomena, no matter whether they are pious thoughts or evil thoughts, domestic thoughts, whatever they may be. One does not relate to them as belonging to a particular category, as being good or bad; just see them as simple thoughts. When you relate to thoughts obsessively, then you are actually feeding them because the thoughts need your attention to survive. Once you begin to pay attention to them and categorize them, then they become very powerful. You are feeding them energy because you have not seen them as simple phenomena. If one tries to quiet them down, that is another way of feeding them...

From the chapter "Simplicity" in The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation by Chogyam Trungpa (Shambhala)

10:28 PM

|

Tuesday, September 16, 2003

Pablo Picasso, Musical Faun #5, lithograph, 1948

I've been looking at a large volume of Picasso's lithographs (Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Munster, The Huizinga Collection) and, as usual whenever I re-encounter Picasso, I'm bowled over by his inventiveness, versatility, and sheer genius. He also makes me laugh out loud. This picture of a musical faun (the artist, perhaps?) is the fifth and free-est in a series of lithographic explorations of fauns playing pipes. It reminds me of some of the Picasso ceramics that were exhibited a few years ago at the Met - did anyone else see them? More works in the days to come...

WORDS CREATE WORLDS, reprise

There's an interesting discussion going on in the comment thread (HaloScan comments seem to be down today, to my annoyance -- please keep trying) from September 14. Do words create worlds? Jack writes: "Words absent deeds have no meaning; are null sets." I think he's right, up to a point - but I agree with Abraham Heschel's point that words can lay the groundwork, create the psychological conditions necessary for deeds to occur - both for good and for ill. I'm very interested to know other people's thoughts on this.

5:13 PM

|

Monday, September 15, 2003

GG#26 George Gudni (Iceland) 2001

ISLANDS

It's Island Day at the Ecotone wiki, where contributors are writing about Islands and Place.

I decided not to write about islands because, for this land-locked dweller of hills and mountains, the essay would have to be a metaphorical exploration of Life as an Island, or some such notion, and it felt like too much of a stretch. So I'm leaving the topic to the excellent thoughts of people who have actually lived on, and know about, the real thing. I do wish I could get my neighbor(s) to write something - they are from Iceland and have a great deal to say about the effect of that island on both the national and individual psyche.

My personal favorites among islands? Manhattan. England. Five Islands, Maine, where I had my only close encounter with the sea, nearly getting dashed against the rocks in a canoe as J. and I tried to paddle around a small island and found ourselves in roiling open water before the entrance to the harbor. And a small unnamed island in Lake Winnepesauke, new Hampshire, whose shore I've roamed in a one-person kayak, listening to loons at dusk.

4:24 PM

|

Sunday, September 14, 2003

PLURALISM

It's a sort of interfaith day for me. After church, I had the pleasure of introducing Susannah Heschel, who was giving a talk about her father and his unique place in Jewish theology to a group of Episcopalians. One of the subjects that came up was the fact that Abraham Heschel was, and is, an inspiration to many Christians. Heschel himself said that in his opinion, "religious pluralism seemed to be the will of God" and that interfaith dialogue was crucial in our world. We should focus "on what we have in common, not what divides us," he said, and his life and work reflected that conviction. Pope John XXIII told him once that his writings "made Catholics into better Catholics", and Heschel was very pleased by this.

In 1965 Heschel gave a lecture at Union Theological Seminary entitled "No Religion is an Island". It strikes me today as very prophetic, especially if we include other religious groups. Here's an excerpt:

Our era marks the end of complacency, the end of evasion, the end of self-reliance. Jews and Christians share the perils and the fears; we stand on the brink of the abyss together. Interdependence of political and economic conditions all over the world is a basic fact of our situation. Disorder in a small obscure country in any part of the world evokes anxiety in people all over the world...

The religions of the world are no more self-sufficient, no more independent, no more isolated than individuals or nations. Energies, experiences, and ideas that come to life outside the boundaries of a particular religon or all religions continue to challenge and to affect every religion.

Horizons are wider, dangers are greater...No religion is an island...

We fail to realize that while different exponents of faith in the world of religion continue to be wary of the ecumenical movement, there is another ecumenical movement, worldwide in extent and influence: nihilism. We must choose between interfaith and internihilism...Should we refuse to be on speaking terms with one another and hope for each other's failure? Or should we pray for each other's health and help one another in preserving one's respective legacy, in preserving a common legacy?

First and foremost we meet as human beings who have much in common...My first task at every encounter is to comprehend the personhood of the human being I face, to sense the kinship of being human, solidarity of being.

To meet a human being is a major challenge to mind and heart. I must recall what I normally forget. A person is not just a specimen of the species called Homo sapiens. He is all of humanity in one, and whenever one man is hurt, we are all injured. The human is a disclosure of the divine, and all men are one in God's care for man. Many things on earth are precious, some are holy, humanity is holy of holies.

The Dalai Lama, not surprisingly, has a similar view. Here's a quote from a recent lecture, via both2 and beyond binary:

Love, compassion, forgiveness, and self-discipline are at the core of every major religion. If you take your own religion at its word and practice it sincerely, you will see and respect those qualities in other world religions. Peace begins with each of us practicing those virtues, mindfully, every day, in our own lives.

2:23 PM

|

WORDS CREATE WORLDS

Words, he often wrote, are themselves sacred, God's tool for creating the universe, and our tools for bringing holiness - or evil - into the world. He used to remind us that the Holocaust did not begin with the building of crematoria, and Hitler did not come to power with tanks and guns; it all began with uttering evil words, with defamation, with language and propaganda. Words create worlds, he used to tell me when I was a child. They must be used very carefully. Some words, once having been uttered, gain eternity and can never be withdrawn. The Book of Proverbs reminds us, he wrote, that death and life are in the power of the tongue.

from Susannah Heschel's introduction to her father, Abraham Heschel's, book of essays, Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity.

12:11 AM

|

Friday, September 12, 2003

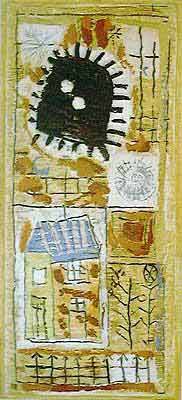

Roger Bissiere, Le Soleil (The Sun), 1960. Linocut printed in 8 colours from 3 blocks

A couple of orders for new (in some cases, used) books have been arriving. I bought my own copies of several of the Polish poets, the Elaine Pagels book, and then, at Powell's, found some used copies of three that sounded interesting: Rozewicz's "The Card Index and other Plays" (he is as well known for his plays and for his poems), and Zbigniew Herbert's "Still Life with a Bridle" (about 17th century Dutch art) and "Barbarian in the Garden", Herbert's essays on the art and culture of France and italy. he, apparently, is "the barbarian". And - synchronicity again - what is the first essay about? Lascaux:

Lascaux is not on any map. It does not exist, at least not inthe same sense as London or Radom. One had to enquire at the Musee de l'homme in Paris to learn its location.

I went in early spring. the Vezere Valley was rising in its fresh, unfinished green. Fragments of landscape seen through the bus window resembled canvases by Bissiere. A texture of tender green.

Breakfast in a small restaurant, but what a breakfast! An omelette with truffles. truffles belong to the world history of human folly, hence to the history of art. So a word about truffles...

I knew nothing about the painter Roger Bissiere. It turns out that he lived from 1888-1964, exhibited regularly at the Paris salons from 1919 on, painting in a Cubist style and then returning to Classical values. He was also a journalist, and wrote the first monograph on Georges Braque, and also published articles on Seurat, Ingres and Corot. There wasn't a lot of his work on the web, but I liked what I saw, especially this portrait and some later abstractions.

4:05 PM

|

I’m working in bed on my brand new laptop. It’s a Dell Inspiron 600 and I love it, but that’s coming from someone for whom hardware is very much a tool and not a particular interest. J. really put it together for me, asking a lot of questions, and I have to say that I’m thrilled and grateful. My work involves increasing amounts of writing, interviewing, research, and the need for wireless access, and this is going to free me from being tethered to my desk. It’s also very powerful and has an excellent screen, so I can run programs like InDesign and work on it very easily. I can also stay in bed late, drink coffee, and write…well, that’s the fantasy!

Maybe you’d like to take a quick peek at my bedside table, all you out there who wouldn’t dream of opening up someone’s medicine chest or sneaking a look into their bedroom. Let’s see: this is going to be a long list, I’m not the neatest person in the world. OK. On the table we have Reading Lolita in Tehran, and on top of that, a red tomato-shaped pincushion, my transparent bug-green traveling alarm clock, and a Canadian “Asia Phone” calling card. A couple of pens, a smoky grey plastic barrette, two emery boards, a brass-handled rubber-tip gum stimulator, a bottle of skin lotion and another one of K-Y jelly. The rest, except for a box of tissues, is reading material: in a pile, a bunch of New Yorkers and Christian Centuries; a spiral-bound notebook; Volume Two of Richardson’s biography of Picasso; Elaine Pagel’s Beyond Belief; and Growing Shrubs and Small Trees in Cold Climates.

Lined up behind a red leather bookend that was always in my parents’ den, we have books partially read: the Beckett Trilogy, Textual Sources for the Study of Islam; Flaubert’s Sentimental Education; Arab Folk Tales; essays by Eqbal Ahmad; Homecoming, by Jiro Osaragi; Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter; Shakespeare’s History Plays; and Thomas Merton’s The Ascent to Truth. Under the tissue box there’s Ulysses (ever hopeful); A Dictionary for Episcopalians, The Chosen, and Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? All the Polish stuff is downstairs on my desk, but it used to be on this table too. On the floor – no books! congratulations! – a pair of cheap red Chinese brocade slippers, my black sandals, and a pair of blue transparent flip-flops.

Groan. I really do have to get up.

8:42 AM

|

Wednesday, September 10, 2003

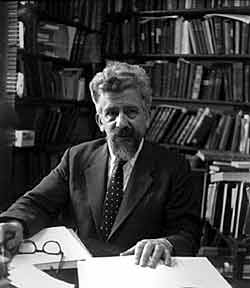

ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL in 1959. From the Ratner Center collection.

Abraham Joshua Heschel, rabbi, theologian, and civil rights activist, was one of the most influential Jewish thinkers of the 20th century. Last night I began reading a book of his collected essays entitled Moral Grandeaur and Spiritual Audacity. I was reading it in order to be able to moderate a discussion on Sunday, but the clarity and directness and relevance of his thought propelled me into a kind of theological devouring that's pretty rare, despite the large number of "spirituality and religion books" that pass across my bedside table.

And of course there is the synchronicity - that word keeps coming up - of finding the writing of this Eastern European Jew, a refugee who lost his mother, sister, and many other relatives in the Holocaust, just when I have been reading all that Polish poetry, mainly by Christians, and searching in it for answers to how people live and maintain faith in spite of senseless suffering. In fact, Heschel's clear explanation of what it means to be a Jew is one of the most enlightening parts of the book. And his impassioned preaching about our work in the world, our reason to be, reaches across all religious boundaries.

I have a feeling that I'll be quoting quite a bit here; for tonight, here's an excerpt:

The Bible is an answer to the supreme question: What does God demand of us? Yet the question has gone out of this world. God is portrayed as a mass of vagueness behind a veil of enigmas, and his voice has become alien to our minds, to our hearts, to our souls. We have learned to listen to every ego except the "I" of God...

9:40 PM

|

Tuesday, September 09, 2003

Young Monks Praying at Polonnaruwa

by Juergen Schreiber at srilanka.com

ANIL'S GHOST

On my road trip, I listened to a six-cassette tape of Anil’s Ghost by Michael Ondaatje.

Michael Ondaatje was born in Sri Lanka as the child of Dutch-Ceylonese parents. He’s probably best known as the author of The English Patient. Eight years after that book won the Booker Prize, he published Anil’s Ghost, about a forensic anthropologist (a woman named Anil Tissara) working for a human rights organization who returns to her native Sri Lanka to investigate the “disappearances” in which thousands of Sri Lankans were tortured and murdered by the warring insurgents and by the government itself. Anil’s story is, in some way, Ondaatje’s story, and it is almost unbearably sad: as the book says, “No one could remember what the war was supposed to be about. The reason for war had become war.” (More on human rights in Sri Lanka)

At first I thought, “can I really stand this as my travelling companion?” But as the story continued, I began not only to be curious about what would happen, and to admire the writing enormously, but to respond to the book’s human, believable, lyrical, and beautiful aspects – it’s a hymn, in a way, to the ancient history of the country, and also to everything about the landscape and people that strike Anil’s senses as she returns with fresh eyes. I too was “going home” to a place that is quite different from where I live now, and filled with my own memories and ghosts. It seemed both odd and comforting to hear someone else’s story, from halfway around the world, for much of the book is personal, and much more involved with absence, dislocation, and return, than with war. It is, most of all, a book about “place” and its effect on personal identity.

Archaeology and ancient Ceylonese art are the other major themes. Along with Anil, there are three other main characters: the archaeology professor who becomes her investigative partner and guide; his brother and alter-ego who has no personal life but is a brilliant surgeon, working inhuman hours to save victims and sew up the wounds of war; and a native artist/craftsman who is one of a long line of eye-painters. I had never known about eye-painting, and when Ondaatje explained it, I gasped.

When the giant Buddha statues are carved and erected, the last task is for the eyes to be painted; only then does the statue become “alive”. There is an ancient ritual connected to this act; only certain masters are allowed to do the work, and they are dressed in particular clothes, surrounded by certain ceremonies, and perform the painting only at a particular time of day. Most importantly, once the painter has climbed the scaffold to the level of the statue’s eyes, he must turn around, and while his assistant holds a mirror, paint the eyes holding the brush behind his head, looking only at the reflected image. As in the Egyptian desert of The English Patient, the ancient stones of Sri Lanka are alive and filled with spiritual significance for Ondaatje. The whole book, it seemed to me, was another attempt to find meaning in the midst of senseless death and suffering: through love, through dedication to one’s work, through efforts toward justice, through art, and through simplicity of life.

I also have to say that I was stunned by the performance of the reader, the actor Alan Cumming; it reminded me how much I love hearing literature read aloud and how difficult it is to do well; this is a spell-binding rendition, eight hours long.

8:40 PM

|

Monday, September 08, 2003

Corn defines central New York State in early September. The corn plants are taller than an NBA center, intoxicatingly fragrant with pollen, deep green of leaves and yellow-brown of tassels, undulating like ocean waves upon the broad valley floors, riding the curves of the hills, following the paths of streams, roads, woods, rivers. There are fields of blue-green cabbages, soybeans, potatoes, pumpkins, and green hay lying striped and cut, baled hay in great drying shredded-wheat packages dotting the fields, or stacked in piles near cowbarns. But the dominant crop is corn, around every bend in the road. It begins in people's backyards and stretches out to the horizon; in one small town the corn fields began on the edge of the sidewalk between two houses. In the evening, when the air is heavy and damp with humidity, you can taste the corn pollen in your mouth from fields two miles away. At night, raccoons and their young raid the corn fields, some never making it back across the highway. And in the morning you can hear the faint honk of geese, feeding in the same fields.

Coming home, I thought about how this landscape's smells, shape, and sounds are imprinted on my body forever. How does that happen, and when? Does it happen to everyone, even if we aren't conscious of it?

One morning, alone for a few minutes, I walked along the edge of the lake in my bare feet, feeling the warmth of the flat flagstones my father has placed along the shoreline and the dampness of the spongy sphagnum growing in the grass. I lay down on my back and shut my eyes, soaking the stones' heat into my back while the sun beat on one side of my face and body, and stretched out a hand, fingers trailing into the water. I felt myself floating into an indeterminate time: was I ten, or sixteen, or fifty? I knew that beyond my fingers, a sunfish would be lurking, curious, staring at my pale flesh. A large spider would be hiding in the stone wall. Overhead, a kingfisher was probably waiting to launch itself, screeching, across the water. These things hadn't changed. I was the one who had -- or maybe not. Maybe not as much as I thought, or feared. I opened my eyes, turned my head, and looked into the water. There was the sunfish, pale yellow and blue, holding itself still and gazing up toward my face, distorted by the surface. I wiggled my fingers. "Come on," I said, quietly. "They're delicious."

8:14 PM

|

Sunday, September 07, 2003

Back safe from my trip - more on that tomorrow. Here's the final post on Rozewicz.

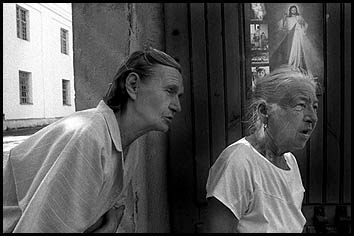

Old Women by Tyocin via photodocument.pl

POLISH POETRY VI: Rozewicz and God, part 3

In the end, Rozewicz comes down on the side of earth and flesh, and praises that which he can: humanity, and specifically those human beings who continue in spite of suffering and calamity. His preference is never more clear than in the poem "Old Women", one of the most famous of Rozewicz’s oeuvre. It’s too long to quote in full, but here are a few representative lines:

old women

are immortal

Hamlet rages in the net

Faust’s role is comic and base

Raskolnikov strikes with his axe

old women are

insdestructible

they smile indulgently

a god dies

old women get up as usual

buy fish bread and wine

civilization dies

old women get up at dawn

open windows

and remove the filth

a man dies

they wash the corpse

bury the dead

plant flowers on graves…

…their sons discover America

perish at Thermopylae

die on crosses

conquer the cosmos

old women go out at dawn

to buy milk bread meat

they season the soup

and open the windows

9:31 PM

|

Saturday, September 06, 2003

Yesterday I drove to New York State to visit my parents. Right now it’s early morning, and I’m still in bed, writing for a few minutes before the spoken part of the day begins. It was a beautiful ride down here, despite the six hours it took and the amount of traffic and late-summer construction. The sky was filled, all day, with huge cumulus and cumulostratus clouds, but giving them their scientific name takes away from their glorious mutability and beauty. The clouds were more than puffy summer cotton balls moving across a blue sky; they were dark grey underneath in places, sometimes extending in rows as far as you could see, othertimes built up to great heights, the sky always varied and dramatic above the blue mountains and green fields. The sun was obscured at times, and then broke through again and again to cast long shadows on fields, nearly chartreuse in the angled afternoon light, with their stacked, round bales of hay or towering stands of tassled corn.

I drove for a stretch along the Erie Canal and Mohawk River, lined with willows. There was a strong, gusty wind, which uncharacteristically whipped up the surface of the water, lending some drama to the usually-languid canal and flat midsection of the state. Further on, I drove along the ridge above beautiful Cherry Valley, site of one of the most murderous Indian raids of colonial times, noticing signs in the distance for the hugely successful Turning Stone Casino, in Vernon, run by the Oneida Indians. My parents ate there recently, with other curious friends. None of them are gamblers, but they wanted to sample the huge Vegas-style day-long buffet and the fancy buildings of the casino; I heard vivid descriptions of marble bathrooms and automatic toilets that retreat into walls, as well as the casino’s prices on gasoline and other commodities. A strange and ironic juxtaposition: the blood, arrowheads and memories held by these fields and valleys, and this new success story by enterprising Native Americans who, by now, understand the white man’s desires and vices well enough to successfully exploit them.

4:47 PM

|

Thursday, September 04, 2003

POLISH POETRY VI

Photo by Alexey Tikhonov from his exhibition “Inhabited Cityscapes”

Rozewicz and God, part 2:

What I come away with is a sense of God’s absence for Rozewicz, rather than annihilation: an absence the poet laments and seems to explain first by God’s inability (or refusal?) to intervene to save human beings in the historical period just experienced, just as he failed to intervene to save Jesus. But God is also absent because he, the poet, voluntarily stepped away and became a creator himself – a poet.

Has Rozewicz lost his faith? I’m not so sure. I think he feels he has removed himself – through sin, through pride, through a worship, perhaps, of words that he doesn’t fully admit? - from a God who may have forsaken him, or at least is so remote as to be unknowable, but he also admits both God’s importance and his own ambivalence in a later poem, from 1988/1989:

Without

the greatest events

in man’s life

are the birth and death

of God

father our Father

why

like abad father

at night like a thief

without a sign without a trace

without a word

why did you forsake me

why did I forsake

You

life without god is possible

life without god is impossible

in childhood I fed

on You

are flesh

drank blood

perhaps you forsook me

when I tried to open

my arms

embrace life

reckless

I spread my arms

and let You go

perhaps You fled

unable to bear

my laugh

You don’t laugh

or perhaps You’ve punished me

small and dim for obstinacy

and arrogance

for trying

to create a new man

new poetry

new language

You left me without a rush

of wings without lightenings

like a field-mouse

like water drained into sand

busy

I missed Your flight

Your absence

in my life

life without god is possible

life without god is impossible

10:04 PM

|

Wednesday, September 03, 2003

POLISH POETRY VI 9.03.03

Sava Sekulic (Serbo-Croatian, 1902-1989) "Angel"

Rozewicz and God (first of three parts)

If the greatest question for critics following WWII has been whether there could be poetry after Auschwitz, a looming question for me has been the fate of God. Poetry continued, as art always continues wherever human being exist. But what happened to belief for these poets of Poland, raised in a strongly Roman Catholic environment among people of deep and simple faith, and then forced to experience not only inhumanity, but a sense of abandonment by that protective God of their youth? Can there be belief after Auschwitz? And if so, in what? How does this get expressed in poetry?

Not surprisingly, among the poets I’ve been reading so far, each individual has a different answer. None were unaffected, and spiritual matters figure highly in their work -- both in determining content, and in the poet’s voice, be it cynical, searching, bitter, existential, loving, transcendent – for we find examples of all of these responses.

Tadeusz Rozewicz, whose work we’ve been looking at most closely so far, speaks of both childhood and simple faith in the same breath. Both are connected with his mother, and both now seem irretrievable:

through the open door

I see a landscape of childhood

a kitchen and a blue kettle

the Sacred Heart

mother’s transparent shadow

the crowing cock

in a rounded silence

(from Doors, 1966)

“Doors” is a poem about the beginnings of sin. The first steps away from the simplicity and innocence of that kitchen are heralded by that crowing cock (a reference to the cock that crowed, as Jesus had predicted, before Peter denied him three times).

It would be easy to call Rozewicz an agnostic, or even an atheist, but I think his relationship to God is far more complex than that. As in Doors, religious imagery and themes appear continually, with Jesus and crosses/trees/thorns/crucifixion perhaps most frequent:

…a tree of black smoke

a vertical

dead tree

with no star in its crown.

(from Massacre of the Boys, Auschwitz,1948)

A wooden Christ

from a medieval mystery play

goes on all fours

full of red spinters

he has a collar of thorns

and the bowed head

of a beaten dog

how thirsty and starved this wood is.

(Wood, 1955) (this is the entire poem)

There are many other references to Biblical stories and imagery including a poem about Job; another about Jesus writing an unrecorded epistle in the sand with his finger; and a powerful poem about the poet himself wrestling with an angel, like Jacob, which ends:

I caught him by the leg

he fell on my dump

under the wall

here I am

a manshaped being

with eyes smashed

to let in

light.

(from A Fight with an Angel, 1959)

There are also personal “confessions” and musing about faith:

I don’t believe

as patently deeply

as my mother

believed

I don’t believe in his altars

symbols and priests…

I read his parables

simple as an ear of corn

and think of the god

who did not laugh…

(From Thorn, 1968)

And there are confessions of sensuality, carnal desire, and the choice to live in real time which take place in religious settings:

In a cathedral

in the rose

in lead

your white nape

hewn from darkness…

…a whisper floats up

damp and warm form your interior

it penetrates the conch of your ear

(from “in a cathedral…”, ~1962)

or this:

honest her arse

is more finely moulded

than

the dome of that famous

cathedral – he thought –

a splendid vessel

temporarily closed

the souls must have been snatched up

by previous generations

and now one has to live

as best one can

shallowly

quicker

(Shallowly Quicker ~1959)

8:08 PM

|

Monday, September 01, 2003

ECOTONE TOPIC: Maps and Place

In my memory, there are always maps. There's the wall of topographic maps in my father’s office, the antique maps of New York State hanging on the walls, the intricately-detailed bird’s-eye views of central New York towns in the late 1800s, the blue school globe in my childhood bedroom – I can still remember the area in the Pacific that had rubbed off - the elaborate fold-out maps from National Geographic, the pull-down maps of the United States and the world hanging in every classroom, accompanied by long wooden pointers that made a hard rapping sound on the blackboard. Later there were specific topo maps for camping and hiking trips, and a boyfriend who sometimes seemed more in love with maps than with me, losing himself in the delicate green lines spread on his dorm room floor: a meditation and escape from the pressures of getting into grad school.

Maps have accompanied all the best road trips of my life, even when the point was to leave the mapped and predictable behind; maps were part of the anticipation, the planning, the excitement of imagining "I will be here – and afterwards, maps became part of memory: “I was there.” Maps settled arguments and solidified dreams; they taught me things I couldn’t see and made me want to see others. And, of course, they were beautiful.

Because I’m a designer, I’ve used maps in publications destined for other people, designed atlases, and even made a few maps myself. Nothing teaches you the real geography of a place better than drawing its map yourself, and nothing makes you more appreciative of the skill and judgment of people who do nothing else but map creation.

Maps represent a lot, but neither are they a place, nor a person; maps are merely tracks on a beach, an enigmatic, tantalizing trail. I wondered today what a map of my present life might look like. There would be an X for my house, with a garden indicated behind it, and some trees, and the street outside, and the field near the river and the grove of thorny locusts. There’d be the bridge across the river, and some roads, big ones and small, not too many, leading to the places where I buy food or go to sing, or buy books, or visit friends. Another X, maybe, for my father-in-law’s house, and my sister-in-law’s, and the church, and the homes of a few friends. Then there would be a road west – that one goes to some mountains and beyond them to the place I was born. And a road north, toward Canada. And a road south, to the big city. And one east, not taken very much, toward the ocean. What would they tell you, these trails across the horizontal plane of my earth?

Do I really exist in these two dimensions, these X and Y coordinates? No, but there’s no map for the rest of me: I can’t draw where I go through this machine, for instance, except to make an undecipherable cross-hatching of more two-dimensional lines, point-to-point. I can’t map for you my past or my future, the flights of my imagination, my dreams, the fragments of poems and paintings or where they came from, and where they go, like the morning fog. It might be better to make a map that shows this room: where I’m sitting with this computer by a southern window that looks out on the street, the place where I eat, the piano, the Druze chest by the door, the window out onto the garden…the location of the blue jay nest under the wild grapevine, the woodchuck hole, the wrenhouse, the yellow jacket nest under the tomatoes. I think it might tell you more. But, then, my map seems to be becoming words.

1:33 PM

|

|

|